How a 24-year-old Educator Became a Principal

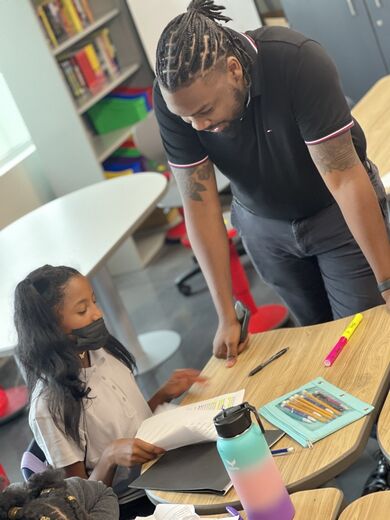

Kenneth Gorham knows that many school leaders are at least two decades older than he is. But he didn’t let that stop him from becoming one of the youngest principals in the nation at the age of 24.

When Gorham accepted the position last year, he also earned the distinction of becoming the youngest principal in the history of Movement Schools, a charter school organization in Charlotte, North Carolina. Now 25, he is far from the typical demographic taking the helm of schools. The average age of U.S. public school principals is 49 years old, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

“We can no longer continue to say people need to be 30, 40, 50 years old before we listen to them,” said Gorham (Charlotte-Piedmont Triad Alum). “We can no longer continue to say that people need to be 30, 40 years old before we trust them to lead us.”

He has a mantra, a question that guides his intentions and motivations as principal at Movement Freedom Middle School: “How do we cultivate and create spaces for our children to authentically be who they are while also adding to their toolkit to promote achievement and success as they matriculate through life?”

Gorham’s own toolkit for growth included finding mentors within the Movement school system and completing professional development such as Teach For America’s Aspiring Leaders Program. Nationally and locally, TFA offers several initiatives to help teachers become administrators.

As he closed in on his eighth month on the job, Teach For America talked with Gorham about the impact of growing up in schools with students or faculty that didn't look like him, breaking society’s implied narrative for principals, and how he realized he was ready to move into leadership.

You started your teaching career at Movement Freedom Elementary School four years ago before moving to the charter organization’s middle school. How did your experiences in those early years as a Teach For America corps member influence the work you're doing now as a school leader?

When I began teaching, I began to see why creating opportunity for all kids is so important. And TFA really exposed us to the importance of that, especially as we did institute (Pre-Service training) in the summertime. I was able to hear experiences that people had as educators and as people in life in general. All of those things really just added to fueling my "why." And why as a principal I'm so intentional behind doing impactful work every single day I enter the building.

The thing that's made me stay at Movement is we have a mission—an objective to love scholars, to value scholars, and to nurture scholars. Movement Schools promote rigorous academics, but I also love the intense value behind cultivating positive character, morals and ethics, educating students on community, the world and society. A kid can get in front of a test and pass and ace it. But are you also pointing to them as a person? Because one day they won't be in your school and they'll be in the world. Are you creating a space that will cultivate them to succeed professionally, academically, but also just be great humans and members of society too? Movement does a really good job of balancing how to pour into the whole child, prioritizing academic success as well as intentional and impactful character development.

You were a fourth grade reading teacher and a fifth grade science teacher before being promoted as an instructional coach and then principal. Can you talk about your intentions behind becoming a principal and how you know you were ready?

I want to lead a school where children can come to the building, feel the spirit of God, feel loved, feel seen, and feel valued. And I want to lead with the belief that if I had children, I would proudly send them to my school. I also want to lead a school because so many of our children face so many societal disadvantages. I think about how poverty is cyclical. I think about how there are poverty mindsets that children even have and they don't even realize it. I think about how so many of them experience things that are truly out of their control but impact their day-to-day experiences. I lost my mother at 12 years old and ended up living in a few different homes up until I graduated high school. There were custody battles here and there which further increased the abandonment I constantly felt. I dealt with the “Oh, my gosh, what do I do now?” A lot of our kids have situations where they say, “What do I do now? There's no way I can make it out.” When I walk into this building every day, I want them to see, yes, you can overcome life’s challenges, because I did it too. I also believe that even though life can be challenging for us, we can’t allow our circumstances to be excuses that we use to believe we can’t achieve success, something I pray my children believe and walk away with always remembering.

I knew that I was ready in my second year of teaching when my North Carolina End-of-Grade (EOG) proficiency scores were the highest across my grade level. Additionally, I became an instructional coach last school year and all the teachers who I coached achieved double digit proficiency growth on the EOG Tests, so I knew there was a level of effectiveness in my instructional practices and leadership. It’s one thing to be a results-yielding teacher, but it’s another to partner with teachers in their coaching and development and see them get the results for their students too. I believe that God is leading me to a place to empower and cultivate children, as well as cultivate teachers as they also prepare to enter the instructional leadership pipeline.

Growing up in Charlotte, North Carolina, what were your experiences like in school? Did you have principals who inspired you and who you could see yourself in?

Growing up, I had one principal who looked like me, Mrs. Jametta Tanner; she was my middle school principal. Mrs. Tanner was one of the first instructional leaders I saw lead in a way that was true to who she was, while also embodying a student-centered mindset for the scholars she served. Throughout my elementary and middle school years, I was in schools where Black and brown scholars were the minority as well as Black and brown teachers and school leaders. When I look at myself as a principal and I look at the scholars who I serve, I'm always very big on showing them that there isn’t anything you can’t do. I truly believe that as humans when we see something, the confidence and belief in it progresses so much because it's something we can see tangibly. When my scholars get to see me as a principal, it's something that they can see and say, “I don't have to hear this in a story or catch it in the news. I can literally come to school every day and see someone who does look like me. I can see someone who's also young, but still going after all of their dreams and desires, even considering their life and the things they've had to overcome to get to this point.”

“Scholars, their well-being and achievement has to be at the forefront of your brain. Why do you do this work? You ask yourself that question every day and let your response, which shows your love and belief in scholars, be the thing that fuels you each and every day you enter the building.”

To prepare for leadership, you completed training through the Relay Graduate School of Education and the TFA Aspiring Leaders Program. Also, you’re currently pursuing a master’s degree in Urban Education from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. What else has prepared you to become a principal?

I'm a very spiritual person and what I’ve realized is that many times we don't realize the innate abilities that God has embedded in our DNA for us to lead. God puts us in a position to be mentored by people and he gives us people who see things in us that we don’t see in ourselves.

Lauryn Jackson, the founding Principal of Movement Freedom Middle School, and the current Principal of Movement Freedom Elementary, was and continues to be one of those people for me. Lauryn has continued to be my mentor even though technically we are now colleagues. Undeniably, she poured so much into me. She created spaces in our work relationship where I was able to unequivocally gain knowledge and expertise based on her highly effective instructional practices and people leadership skills. Lauryn let me lead, affirmed the moments of success, while also partnering with me consistently where there were opportunities for growth. Lauryn, to date, remains the strongest instructional leader I have ever worked for, or experienced in the field of education and I count it a true honor and blessing that God allowed our paths to cross. With her remarkable mentorship, along with who God has already created me to be, I was able to operate and show up yielding results as an instructional leader.

At 22 and 23 years old, I was able to coach and develop teachers so much that they received 20 percent-plus growth year-over-year on their EOGs in reading and math. Currently in my first year as a principal, my sixth grade English language arts cohort–led by one of my phenomenal teachers, TFA alum Tyler Adams (Charlotte-Piedmont Triad Alum)–had a 42 percent cycle to cycle growth from quarter 1 to quarter 2.

Interested in Joining Teach For America?

Take a quiz to see if you're eligible

What do young educators need to help them prepare for administration school leadership roles?

Young educators need consistent introspectiveness, reflectiveness, and need to see children beyond what they come into classrooms with. I think consistent coaching and development from instructional leaders is pivotal for novice teachers. When I'm coaching teachers, I’m always thinking, is this a skill building moment for them? How is it going to cultivate their development so that when they do want to branch off into leadership, they are ready? But novice teachers also have to be ready to receive very direct and honest feedback about their performance because inevitably it impacts scholar achievement.

I believe that as a country we have not done as well of a job with prioritizing the roles that educators place in society. As a nation, I believe that paying our teachers more would be a phenomenal thing to do. When you consider that in every field, every profession, every walk of life, everyone was taught by a teacher, why are we not prioritizing the field of education?

What advice would you give to teachers who want to step into leadership?

You're going to have people who don't feel like you deserve to be in your seat. You're going to have people who feel like you're doing too much or not doing enough. Scholars, their well-being and achievement has to be at the forefront of your brain. Why do you do this work? You ask yourself that question every day and let your response, which shows your love and belief in scholars, be the thing that fuels you each and every day you enter the building.