The Crushing and Inequitable Burden of Student Debt

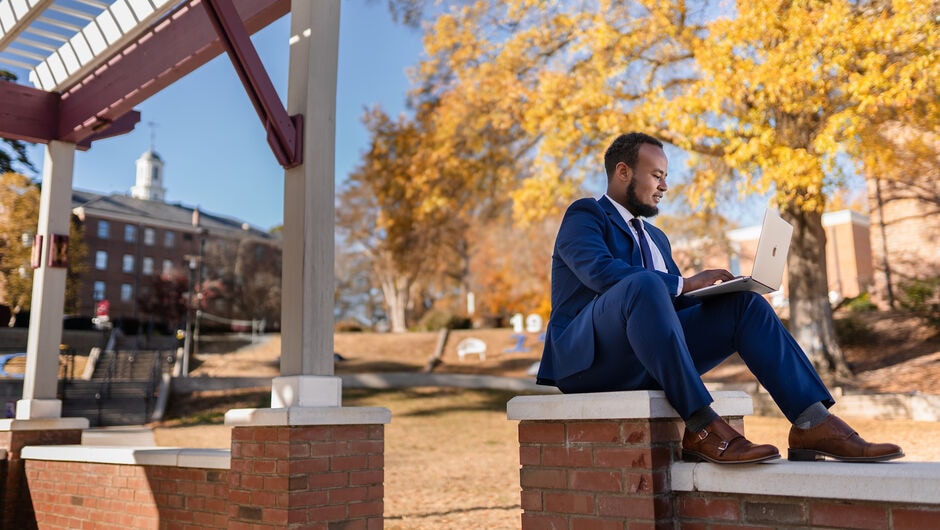

Manuhe Abebe had a lot on his plate going into last summer: two full-time internships, summer classes, and plenty of stress over how he would pay off his outstanding student balance at North Carolina Central University.

Then in July, he received an email from NCCU that said the balance of his tuition and fees—$5,000 in total—would be cleared. It was an immediate relief.

“I was able to do things that I wouldn't normally do, like invest in my education, buy a laptop, buy a new phone,” said Abebe, 19. “I’m in student government, so I was able to go ahead and buy my first full suit, you know, with dress socks, dress shoes.”

Abebe is benefiting from an emerging student debt relief trend: Historically Black colleges and universities, minority-serving institutions, and community colleges are using emergency COVID-19 relief funds from the American Rescue Plan to clear millions of dollars of unpaid student balances—actions that benefit Black students and other college students who are most likely to be impacted by the student debt crisis. NCCU alone cleared more than $10 million “in outstanding tuition and fees and waived costs for its summer session for more than 5,200 students,” according to a news release. Since May, students at other HBCUs have had their balances partially or fully forgiven.

Debt relief has also helped address racial inequity. More than 43 million borrowers collectively owe $1.6 trillion in student loan debt, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Black college graduates bear the greatest share of that burden. On average, Black college graduates owe $25,000 more in student loan debt than their white peers, according to The Century Foundation, a progressive think tank.

But recent attempts to forgive student debt for students disproportionately impacted by the crisis will only last until COVID-19 relief funds dry up. They are triage for a chronic problem. While many current and former college students have found temporary relief from the burden of student loan payments—the Biden administration recently extended a moratorium on federal student loan payments, spurred by financial hardships brought on by the pandemic, until May 1—long-term solutions to the student debt crisis don’t appear to be on the immediate horizon. Advocates and policymakers have put forth a number of solutions aimed at making college more affordable—from lowering loan interest rates to making public college free—but a lack of formal executive or legislative action is causing borrowers to wonder what happens after May and beyond.

How will tens of millions of student loan borrowers manage their growing debt? What will policymakers do to close the racial wealth gap exacerbated by this crisis? How will future generations of college-goers afford to get the degree they need to land a higher-wage job?

An Inequitable Burden

Student loan debt disproportionately affects Black borrowers because of the racial wealth gap. The average white household in the U.S. has about 10 times more wealth than the average Black household. Without generational wealth to rely upon, many Black families have to take on a lot of debt to finance a college education.

Black college graduates are also more likely to hold private student loans, which do not offer important borrower protections like income-driven repayment plans, and they are more likely to attend predatory for-profit colleges associated with high loan default rates.

The result: The racial wealth gap is widening and higher education is contributing to it, according to sociologist Louise Seamster. For households with student debt, the average white household has 20 times more wealth than the average Black household.

“You're using that higher income to help pay for your parents to retire, to help pay for your grandma to go through open-heart surgery,” Romer said. “You're not actually able to build wealth.”

And while college degrees do help Black households to grow their income, there is a fragility to this newly acquired middle-class status, said research assistant Carl Romer of the Brookings Institution. Due to generational wealth, white individuals are more likely to receive financial assets from family after graduating college such as an inheritance “to start growing and building their wealth,” Romer explained. Black people, on the other hand, are more likely to be expected to start supporting their families while also paying down student loan debt after completing college.

“You're using that higher income to help pay for your parents to retire, to help pay for your grandma to go through open-heart surgery,” Romer said. “You're not actually able to build wealth.”

It is out of concern for this wealth gap that Trinity Washington University—a predominantly Black institution and a Hispanic-serving institution in Washington, D.C.—used its COVID-19 relief aid to pay off $2.3 million in tuition and fee balances for its 535 undergraduate students in 2021.

“Relieving the financial stress is definitely a racial equity issue,” Trinity Washington University President Pat McGuire said. “We know that Black women carry the highest student loan debt burden in the country. That debt burden prevents them from doing things that can improve their economic condition, like buying a home and accumulating wealth in real estate.”

Finding Long-Term Solutions to the Student Debt Crisis

Advocates are seeking ways to reduce the cost of college for generations of college-goers who are deeply concerned about how they will be able to afford to pursue an education.

Maheen Ahmed, 23, is very familiar with this anxiety. When it comes to pursuing education or investing in her career goals, her first worry has always been: “How am I going to pay for it?”

Pursuing a college education has been a complicated process for Ahmed, a first-generation college student who holds a full-time nannying job to pay to attend Howard Community College in Columbia, Maryland. In her freshman year, Ahmed, then 18, struggled to attend class while working full time. A year and a half later, she was placed on academic probation and was ineligible for financial aid until she improved her grades. Today, Ahmed is an honors student with a 4.0 GPA and president of the college’s student government association, but she still remembers her difficulties paying for school out of pocket while under academic probation.

Concern over how she will pay for her education was a “survival instinct” for Ahmed. That’s why when Ahmed received an email stating that her debt would be cleared by HCC, it was almost too good to be true. “The fact that I didn't have to pay $1,200 out of pocket was extremely relieving,” she said.

“We know that Black women carry the highest student loan debt burden in the country. That debt burden prevents them from doing things that can improve their economic condition, like buying a home and accumulating wealth in real estate.”

To help offset the rising costs of college education, some advocates have proposed expanding Pell Grants, which are a form of financial aid for students from low-income households that does not require repayment. Pell Grants once covered nearly 80% of college costs, but now they cover less than 30%, according to The Institute for College Access and Success.

“It has not kept pace with the cost of college,” McGuire said of Pell Grants. Some proponents are hoping to change that through campaigns like Double Pell, a coalition of education groups that seeks to double the maximum Pell Grant by the 50th anniversary of the creation of the program in June.

“Double Pell is a movement right now, and I believe it is absolutely imperative,” McGuire added. “Doubling it up to $13,000 would be a tremendous piece of leverage to keep students in school.”

Other proponents seek to alleviate the burden of college loan repayments by ending predatory private lending practices. On Jan. 13, student loan servicing giant Navient reached a $1.85 billion settlement with 39 states over claims about the company’s predatory student loans. The charges against Navient include issuing subprime loans to borrowers unlikely to pay them back, charging interest rates as high as nearly 16%, and steering students away from federal student loans relief programs, according to The Washington Post. The company was ordered to cancel $1.7 billion in private student loan debts to 66,000 borrowers nationwide and pay an additional $95 million in restitution payouts.

Abebe believes that NCCU’s decision to clear student balances will have a profound impact on the school’s student body. “I think it really helped me and my peers really think about ourselves a lot more and what we want to do after college, things that we are dreaming about,” he said.

photo by: Jerry Wolford and Scott Muthersbaugh / Perfecta Visuals

Abebe believes that NCCU’s decision to clear student balances will have a profound impact on the school’s student body. “I think it really helped me and my peers really think about ourselves a lot more and what we want to do after college, things that we are dreaming about,” he said.

photo by: Jerry Wolford and Scott Muthersbaugh / Perfecta Visuals

Abebe believes that NCCU’s decision to clear student balances will have a profound impact on the school’s student body. “I think it really helped me and my peers really think about ourselves a lot more and what we want to do after college, things that we are dreaming about,” he said.

photo by: Jerry Wolford and Scott Muthersbaugh / Perfecta Visuals

Abebe believes that NCCU’s decision to clear student balances will have a profound impact on the school’s student body. “I think it really helped me and my peers really think about ourselves a lot more and what we want to do after college, things that we are dreaming about,” he said.

photo by: Jerry Wolford and Scott Muthersbaugh / Perfecta Visuals

There are also calls from advocates to revamp existing income-based repayment programs to be more affordable, streamlined, and include private student loans and federal Parent PLUS loans—both of which are ineligible for existing income-based payment plans.

One of the most ambitious short-term solutions to the student debt crisis policymakers are considering is debt cancellation. President Biden vowed on the campaign trail to cancel at least $10,000 of student debt for all borrowers—a promise that has not yet been delivered—while some Democrats have called for President Biden to forgive up to $50,000 per borrower via executive action.

The Biden administration has canceled some forms of student debt—albeit for only a small percentage of borrowers. In August, the administration announced it would forgive $5.8 billion in student loans for over 300,000 borrowers with disabilities and $1.1 billion in student loans for students defrauded by for-profit schools.

But some, like Romer and his colleagues from the Brookings Institution, worry that a solution that focuses solely on one-time debt cancellation would only solve the student debt crisis—and the growing racial wealth gap caused by this debt—in the short term. Future generations of students would still need to take on debt to finance their education if the issue of college affordability is not addressed.

“We need to make sure that we're not kind of replicating the same mistakes that we've made in the past,” Romer said. That’s why, in addition to full debt cancellation, Romer and his colleagues propose making public two- and four-year colleges tuition-free.

“We need to make our society more equitable,” Romer said. “Making college tuition-free for the future will help a whole swath of students and prevent the type of inequality that has manifested through our current system.”

What the Student Loan Debt Crisis Is Costing Students and Society

For students seeking to secure a better future for themselves by earning a college degree, the student debt itself can become an unexpected obstacle to achieving their dreams. Recent examples of debt forgiveness—from HBCUs clearing student balances to Robert F. Smith’s historic $34 million gift to Morehouse College’s graduating class of 2019—provide a glimpse into what could be possible for students and society if the student loan debt crisis were addressed.

During his freshman year, Abebe spent most of his time applying for scholarships and worrying about his financial stability. But since his student debt at NCCU was forgiven, Abebe has been able to go into his sophomore year focused on academics, internships, and his aspiration of becoming a venture capitalist and increasing the number of Black professionals in the industry.

“It definitely gave me a chance to really focus on my future,” Abebe said.

Clearing student debt helped Ahmed, the Howard Community College student, to prioritize her ambitions in computer science and what comes next in her career. “It just really allows me to focus on, ‘OK, like what does Maheen want to do with herself?’”

Student loan debt hinders both personal ambitions and society at large, Romer explains. For example, debt-burdened students sometimes avoid lower-paying public service careers.

“We're not getting the benefit of people who may feel a real passion for teaching, for public defense, for social work,” Romer said. “All of these career paths that may not pay high monetarily, but have a socioeconomic benefit of giving back to one's community. These people who have student debt can't make that monetary sacrifice because they need to pay these debts back.”

This tug-of-war between paycheck and passion is something that Abebe and Ahmed have both personally experienced as college students preparing to enter the workforce. “I think student debt really plays a role in your career,” Abebe said. “Because a lot of kids do have a dream job. And that dream job may be, you know, to become a teacher. But people are now rethinking like, ‘OK, what is the fastest way for me to make money right out of college?’”

The need to earn a living, she said, is definitely keeping students from being as ambitious and innovative as they can be.

But, Ahmed added, there’s a way for officials to address this problem: “If they want the youth to be innovative and believe that they can change the world, one thing they can do is help relieve any sort of student debt.”