From The Classroom To The Clouds: Lincoln Boyd On What It Means To Serve

When asked, Lincoln Boyd (Mississippi ‘15) can trace the journey from his own education to his choice to join Teach For America by way of a number of crossroads. He reached the first when transitioning from his high-performing, private K-8 school to high school, and the trying choice between another high-performing, private school and a lower-performing, public school became clear.

“My decision to go to a different high school kind of ate away at our family unit,” Boyd says, as he explains first noticing the catch-22 of his situation: attend a school that would nearly guarantee his college acceptance but which his family could not afford, or attend a school with fewer resources and opportunities and spare his family’s spending. Fortunately for Boyd, a third option arose. He was offered a place in the private school at a subsidized price if he and his family enrolled in a summer working program. However, when Boyd entered this program he further noticed that it was predominantly populated by people of color. He then realized the catch-22 extended to more than just him: “Why is my family the only white family in this program? Why are the other people in this program the only people of color at St. Mary's [the private school]? And why were the majority of students at Tokay [the public option] people of color, even though the demographics of the two communities were basically identical?"

In search of answers to these questions that would go beyond his own experience, Boyd shaped his college career around the study of educational inequity. At Lewis and Clark, he pursued studies in education policy, and jumped at opportunities to expand his lens by studying abroad - administration and school turnaround programs in Shanghai, and teacher training programs and education funding in Finland. Still, it was hard to resist the obvious question: if it’s working in these places, why couldn’t it work here?

His college graduation presented another crossroads: join the Navy or join Teach For America? For some, this may not seem like two comparable options, but for Boyd this amounted to two of his greatest passions, in service of one: serving others.

Boyd describes this time in his life through the eyes of his grandfather, who, though quite supportive of Boyd’s choice to apply to Teach For America, was himself a Navy man. Boyd recounts his grandfather’s story of joining the Navy in 1943, and becoming entranced with the B-52 bombers he witnessed being used by his peers. From then on, his grandfather dreamed of becoming a pilot, even while pursuing advanced training in electrical engineering and serving his country in other ways. In fact, he did not achieve his dream of earning a pilot’s license until much later in life, surprising his wife after sneaking their children off to help him earn his requisite flight time. This story of self-sacrifice, coupled with Boyd’s father’s own put-off dream to fly, stuck with Boyd from an early age.

But, at the juncture between the Navy and TFA, he chose TFA. He felt that it would serve as the culmination of his education, while letting him exercise his passion for people. “And, if I’m going to be fighting for educational equity,” Boyd says, “why not do it in Mississippi, which shows up last or close to last on nearly every education ranking?” Mississippi would serve as an ideal lens into seeing a rich history of race and class tension as well as education inequity - while giving Boyd an excuse to dive into the world of the blues, a world with which he’d been obsessed since he was young. Though Boyd had never been to Mississippi before joining TFA, much less the Delta, he was happily placed in the heart of the Delta Blues, the crossroads itself: Clarksdale.

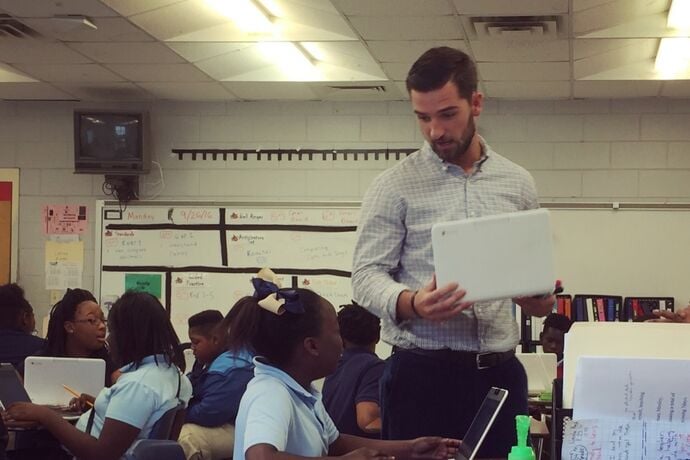

Boyd recounts his two-year commitment with unbridled joy. “It certainly had it’s challenges, there’s no denying,” Boyd says, “I am forever indebted to my students.” Yet the support he felt, the connections he was afforded, and the opportunity to engage with so many inspiring, brilliant students left him with an undeniably positive impression. His favorite classroom moment was with a student whose brilliance, Boyd admits, took him by surprise. He describes a girl gazing out the window, looking away, at anything or anyone but him during class. “She never appeared to be paying attention, but she was, she really was!” She showed mastery of the material they covered, excelling at every assessment he put before her, but one day she stormed up to him, graded test in hand. “What does this mean?” she’d asked, pointing to the “You’re going places!” excitedly written at the top of her paper with her grade. He explained that this meant that she did well, that her grades would take her wherever she wanted to go - “you’re going places, you’re doing stuff,” he summarized. Her expression immediately changed from frustration to elation. “I’m going places, I’m doing stuff!” she repeated, and the quip quickly became her mantra. Hearing his student take to this description of herself was a powerful lesson for Boyd: “These students are so smart, and I’m here to remind them of that.” Boyd’s selflessness and directness made an impression on his community as well, including the folks at Pete’s Wings, Boyd’s favorite spot in Clarksdale. Boyd recounts spending regular Friday nights at the counter, talking to the owner for hours, and it was this real connection that earned Boyd trust as the coach of the owner’s own child, as well as a big Pete’s Wing sendoff at the end of the school year.

As he neared the end of his two year commitment, Boyd approached one more crossroads: stay on in the classroom to teach a third year, then join the Principal Corps through the University of Mississippi and commit to five years in administration, or join the Navy. Both would require years of commitment, and both would afford Boyd the opportunity to expand his horizons. He decided to apply to the Navy’s pilot program, just to see if his aptitude in mathematics and physics would make the grade, and, though he expected little of himself, his scores were remarkably high - high enough to help make his choice for him.

He resolved to join the Navy, to the delight of many, and the chagrin of many more. “It seemed like the people who were supportive and the people who weren’t all did so for the wrong reasons,” Boyd says. His friends and family were concerned about the world climate, and what that might mean for Boyd’s safety. To others, it seemed like his military service would take him in a direction philosophically opposed to his experience in the classroom. To Boyd, however, the two experiences were in more alignment than people realized, and amounted to the whole of his personal theory of change, which requires leaving the familiar in a selfless search of answers to the bigger questions, and, more importantly, putting others first. This opportunity would fulfill that theory of change by continuing his personal development, offering “the allure of studying a new craft,”and “greater exposure to global affairs, to see what’s going on with the world.” More so, as Boyd puts it simply: “Public service fulfills my sense of purpose. I really do feel like this is a chance to continue to serve my country, maybe in a different capacity."