40,000 Students Have Spoken: Here’s What They Have to Say About Their Classroom Engagement and Agency

Introduction

Following the pandemic, it became clear that a rising number of k-12 students view school as irrelevant. Increasing absenteeism and widening learning gaps underscore this issue. And yet, as a field, we still aren't doing enough to ask students how they are experiencing their learning in classrooms and schools. Based on the strong conviction that student feedback is the first step in creating more rigorous, welcoming, and engaging classrooms, Teach for America has implemented a validated student survey about students’ learning experiences and learning beliefs in classrooms across the country.

Last year was our second year of scaling this survey, leading to data collected from over 40,000 students in urban and rural schools in under-resourced communities across the US. We are using these results to explore students’ learning conditions and their resulting learning beliefs, and we are uncovering patterns that are helping us support teachers in fostering students’ engagement and agency over their own learning. Below we share some early insights from this work.

As a field, we've made progress in understanding the importance of students’ learning beliefs for their own development. Now it’s time to sharpen how we measure student learning beliefs.

We started this project as a way to build on the work done recently by Jenny Anderson and Rebecca Winthrop in their popular book, The Disengaged Teen. In this book, the authors explore reasons for growing student disengagement from school. They identify four Learner Profiles students adopt throughout school that are rooted in their learning beliefs related to engagement and agency (see Figure 1):

Resisters—express frustration and push back against learning, often feel inadequate;

Passengers—coasting through school with the bare minimum; believe schooling is pointless;

Achievers—high-performing but driven by external validation; fear of failure makes them vulnerable to mental health issues; and

Explorers—driven by curiosity, initiative, and a desire to learn; exhibit mindsets and strategies that fosters resilience and promotes lifelong learning.

The authors believe that teachers and parents can and should strive to shift students’ learning beliefs in order to foster more Explorers who are engaged in their learning and actively seek to shape their own educational experience, an argument well supported by research.1

The Disengaged Teen provides a helpful framework for thinking about Learner Profiles, however operationalizing it with student data proves more challenging. In the book, the authors created Learner Profiles using a survey of student perspectives about their school experiences, with questions such as, "At my school I can choose how to do my work". Thus, the Learner Profiles are more of a reflection of the school learning conditions than students' actual learning beliefs about their own sense of agency and engagement.

We use a different student survey, which allows us to better approximate how students fit into this theoretical framework based on questions on their actual learning beliefs.2 The survey also includes questions about student experiences in the classrooms, allowing us to begin to explore the relationship between the student Learner Profiles and student experiences in the classroom.3

We found that 40% of students are Explorers; a promising finding, yet most students still report a lack of engagement, a lack of agency, or both.

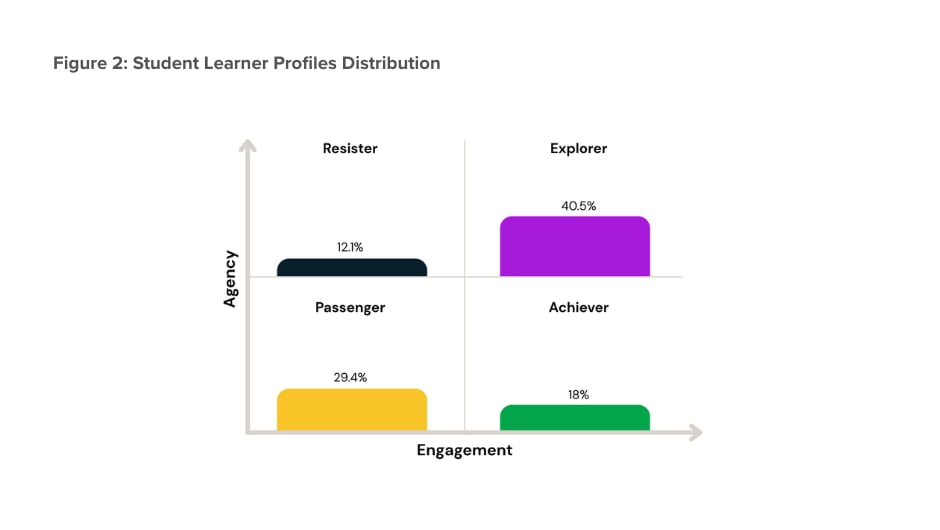

We find that, in our sample of students, three-quarters of whom identify as students of color and all of whom attend under-resourced schools:

- The largest group of students in our dataset exhibit an Explorer profile (High Engagement and High Agency): 40%.

- The second largest group exhibits a Passenger profile (Low Engagement and Low Agency): 29.4%

- The remaining students are split between an Achiever profile (High Engagement and Low Agency): 18%; and a Resister profile (Low Engagement and High Agency): 12.1%.

Our results are more optimistic than what was found in The Disengaged Teen’s companion brief, which reported that 7% of students fit the Explorer profile and 44% of students fit the Passenger profile. This could be the result of differences in the sample of students surveyed as well as differences in the survey items themselves, since the Disengaged Teen’s findings are more of a reflection of the attributions of the school as opposed to the learning beliefs of the students.

It is encouraging that such a large number of students in our sample report high engagement and high agency. However, a sizable percentage (30%) are reporting both low engagement and agency. Research is clear that lacking agency and engagement is linked to lower achievement, higher absenteeism, and higher drop-out rates.4 Furthermore, we find that 18% of students want to learn, but are feeling a lack of agency in their classrooms, which can also lead to a cycle whereby, feeling a lack control or choice in their learning, students are more likely to disengage emotionally and behaviorally in the future, leading to decreased motivation and persistence. And finally, we find that 12% of students are using their agency but are telling us that their classrooms are not engaging. It’s time we listen.

The middle school slump is real–and we need to pay attention to it.

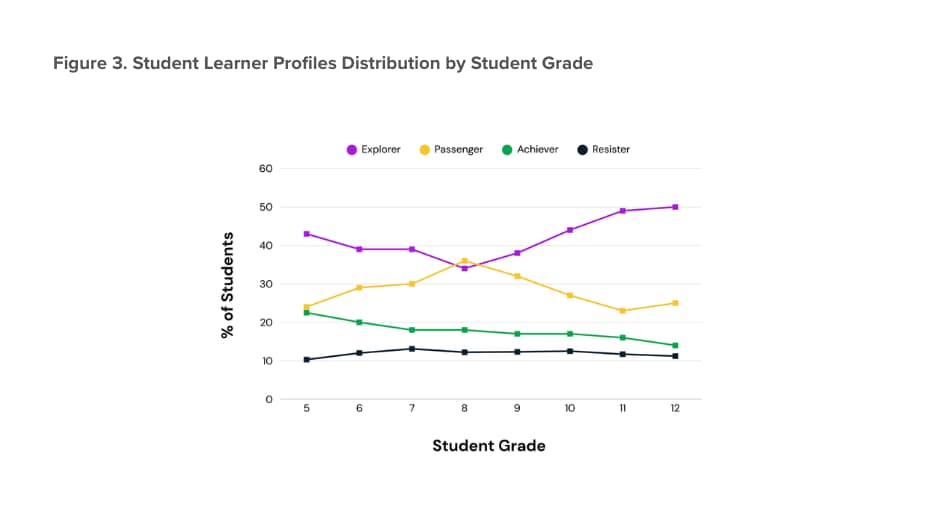

In Anderson and Winthrop’s book, a prevailing theme is that student engagement drops from elementary to secondary school; their findings indicate a decline in the percentage of Explorers from elementary to middle school, and a steady percentage of Explorers from middle school through high school. In our dataset, we also see a decline in the percentage of Explorers from elementary to middle school (43% in 5th grade and 39 to 34% in 6th through 8th grade; see Figure 2 below). However, that pattern reverses as students progress from middle school to high school (38% to 49% in 9th through 12th grade).

This middle school slump is born out in recent studies on student learning beliefs.5 In one study on students’ self-reported learning beliefs, the authors posit that the reason for the middle school slump is that students’ “needs in early adolescence may be mismatched with the contexts around them but are better matched during high school.” As further reinforced by The Foundations for Young Adult Success:

“Taking a developmental lens is essential to ensuring that structures and practices meet the developmental needs of the young people being served. Although a lot is known about development, too often, there is a mismatch between the structures or practices in a youth setting and the developmental needs of the young people being served. Schools, youth programs, and even families are too often oriented to adult needs and goals (e.g., maintaining classroom discipline) instead of taking a youth-centered approach.”

It is time that we pay close attention to how schools can tailor their approaches to students based on their developmental needs, recognizing that the middle school years are a pivotal time requiring a different orientation to child development that focuses on adolescents’ need for agency and identity formation.

What we CAN influence are the learning conditions students are exposed to—and this could unlock more Explorers.

Research shows the importance of classroom learning conditions in fostering student beliefs about themselves as learners. For example, a study by Dr. Camille Farrington, from the University of Chicago, and her colleagues found that:

“[When] a student’s classmates rated the classroom environment of one class more highly than another, the student reported feeling more belonging, more motivation, less of a fear of attracting negative attention, better organization and time management, more self-monitoring of their learning, a greater likelihood of getting homework done before doing other things, and better participation in the more highly-rated classroom—and in turn, earned a higher grade in that class than in the lower-rated classroom.”

In other words, the same student reported stronger learning beliefs in classrooms with stronger learning conditions than in classrooms with weaker learning conditions.

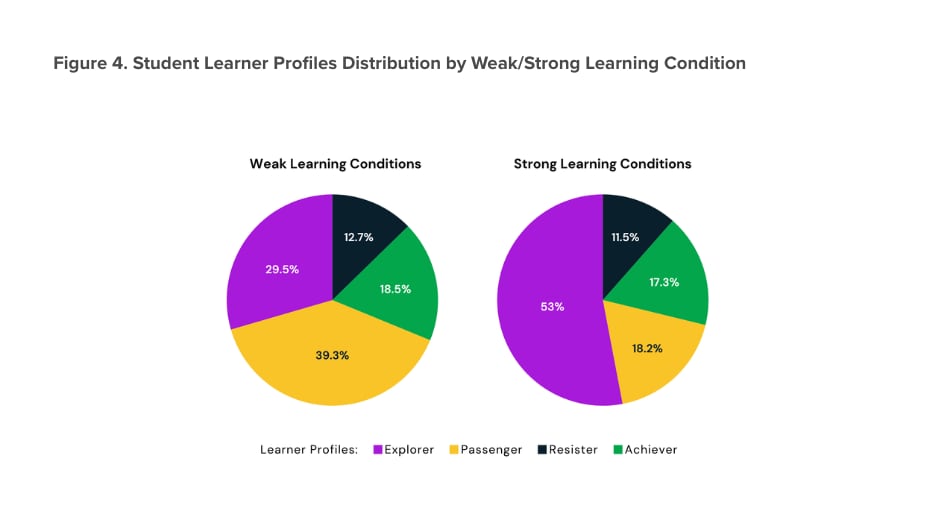

To explore this further, we examined whether Learner Profiles varied based on the types of classroom conditions teachers were fostering. Our survey allows us to examine this because, in addition to questions on students’ learning beliefs, it includes questions about the learning conditions students are experiencing in their classrooms.6

We find more Explorers in classrooms with strong learning conditions (53%) compared to weak learning conditions (29.5%), and more Passengers in classrooms with weak learning conditions (39.3%) compared to strong learning conditions (18.2%) (Figure 3). Interestingly, we didn’t find much of a change in the percentage of Achievers and Resisters across the weak and strong classrooms.

While our results are descriptive, not causal (i.e., our results do not tell us whether strong learning conditions lead to strong learning beliefs), a large body of evidence has demonstrated the causal impact of learning conditions on student learning beliefs. And we do know that collecting student survey data on students’ learning experiences and learning beliefs is the first step in ensuring student feedback is used to inform teacher practice. At Teach for America, we are committed to prioritizing the collection of student feedback to inform coaching conversations with our novice teachers that foster their ongoing development.

Closing

While we find a large percentage of students in our sample are exhibiting strong learning beliefs, the majority of students fall under the other three Learner Profiles, reporting low agency, low engagement, or both. This is particularly true for middle schoolers. This means we have more work to do to ensure all students are developing agency and engagement across grade-levels. As a field, we must commit to elevating student voice and agency, and fostering greater student engagement, in order to create classroom experiences where all students feel engaged and can develop as strong learners, to overcome the rising learning loss and absenteeism resulting from the Pandemic.

End notes

1. See Lei et al., 2018; Vaughn, 2020; Fraysier, Reschly, & Appleton, 2020; and Holquist, Mitra and Connor, 2025.

2. We utilize a research-backed and validated survey developed by the University of Chicago called Cultivate for Coaches. More information on the survey can be found here.

3. For more information on the measures, analyses, and research supporting the insights included here, please reach out to Katie Buckley at Katie.Buckley@TeachforAmerica.org.

4. See Farrington et al., 2015 and Wang and Fredericks, 2015.

5. See Fahle, Lee, & Loeb, 2019 and Rimm-Kaufman, Soland, Kuhfield, 2025.

6. To estimate the learning conditions for each student’s classroom, we calculated the average teacher-level score across the learning condition constructs. We classified strong Learning Condition classrooms as those with average scores in the top half of the distribution and weak Learning Condition classrooms are those in the bottom half of the distribution.