Examining Learning Through an Anti-Racist Lens

A look at how schools across the country are reexamining their curricula to ensure their content and delivery are centered on equity.

Janelle Silva is an associate professor of psychology at the University of Washington Bothell and studies equity issues in K-12 classrooms. During a research project working with second graders in Southern California—many of whom were children of Latinx farmworkers—she remembers the standardized test question that baffled one of the students.

The question showed an illustration with a series of objects, and asked students to identify which one was a “centerpiece.”

“It was a very traditional looking centerpiece that you would see at Thanksgiving, with the big squash,” Silva says. “I knew this student very well. His parents are farmworkers. I know they don't have centerpieces at their house. I didn't grow up with a centerpiece in my house. You're asking him a very colonized question, as simple as picking a centerpiece. And he doesn't know what that is.”

Whether intentional or not, racism can be present in a curriculum in myriad ways. It can show up in standards and test questions that center white colonial narratives. In the lack of racially diverse authors on summer reading lists and library shelves. In the way historical events are framed and whose perspectives are considered. In the amount of time students have to explore their own identities and those of others. And in the extent to which students and teachers do or do not engage in discussions about racial justice and how racism plays out in society today.

In a 2017 report titled “Teaching Hard History,” the Southern Poverty Law Center found that most popular textbooks fail to comprehensively cover the history of enslaved people and white supremacy’s role in American slavery, stating that “state content standards are timid and fail to set appropriately high expectations.”

For example, some students learn about slavery primarily through “feel good” stories about Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad or via the perspectives of white abolitionists and enslavers, rather than the perspectives of the enslaved, the report says.

Other subjects can also include opportunities for students to develop their consciousness for how other fields are shaped by systemic racism. A unit on health, for example, that explores the role of racism in disparities in medicine, such as the high Black maternal mortality rate, can help students begin thinking about how to interrupt these systems.

When a curriculum leaves out perspectives and narratives, all students miss out on building context and meaning around the role that racism has and continues to play across our systems. And for Black, Indigenous, and students of color in particular, engaging in learning that diminishes, misrepresents, or fails to address the complexities of their histories and lived experiences can be painful, and in some cases, cause emotional trauma.

Many schools have taken steps to reexamine their curricula through an anti-racist lens and adjust or fully revamp the way they teach as a result. This work isn’t new. But ongoing national uprisings against systemic racism and police brutality as well as student-led activism have sparked renewed energy among schools to take a closer look at where their curricula may be falling short.

Schools are approaching this work in different ways, seeking input from students and parents, working with diversity and equity experts, asking hard questions, and making changes large and small. It’s part of the ongoing, often messy work to create a more equitable learning environment by uprooting systems that favor one group of students over another. The end goal is for all students to have the opportunities they deserve to get an excellent education.

Interrogating Curriculum

Equipping all students with the knowledge they need to succeed in the real world outside of school means ensuring a curriculum includes the diversity of perspectives that are found in that real world. It also means naming the unjust systems and historical oppression against marginalized communities, while also celebrating the joy of Black, Indigenous, and people of color. Many educators are taking a hard look at a curriculum to identify whose perspectives are overrepresented and whose perspectives may be missing.

At S.T.A.R. Academy-PS 63 in New York City, more than half of the school’s pre-K through fifth grade student population identifies as Black or Latinx. And while the school leadership team always had a focus on equity, they also realized that the school’s teachers—the majority of whom are white—had different levels of comfort when it came to discussing and teaching about race. After a few teachers raised the issue a few years ago, the school launched its Equity Team and kicked-off a formal school-wide effort to interrogate their school’s policies, practices, and curriculum through an anti-racist lens.

The school engaged with the Center for Racial Justice in Education to launch the work, starting with professional development sessions on the four “I’s” of oppression. Staff delved into learning and unlearning how systems throughout our history such as inequitable access to education, housing policy, and voting rights are built on racist ideology.

Building on this foundational knowledge, staff later broke into small groups and evaluated the school’s culture using an anti-racist organization continuum. Jodi Friedman (New York ‘04) is the school’s assistant principal and says the exercise was an important starting point for the school team to identify what steps they could take to grow.

“That was fascinating because we had lots of people say, we're a fully inclusive anti-racist multicultural organization. And other staff members who said no, we are passive at best,” Friedman says, referring to different stages of the continuum. “That helped to start the conversation.”

After laying this groundwork, the school team began evaluating its curriculum and standards through a multicultural curriculum framework. On one end of the continuum is the “curriculum of the mainstream,” focused on Eurocentric and male-centric perspectives. On the other end is a curriculum that addresses social issues, including racism, sexism, and economic injustice.

Teachers were also paid for the time they spent over the summer deepening their learning about a marginalized group of people. They then revised one of their units, incorporating this new knowledge and designed opportunities for students to engage in meaningful conversations.

Erica Lefkowitz teaches kindergarten at S.T.A.R. Academy and chose underrepresented families as her focus. Together with her co-teacher and students, she helped lead an audit of the classroom’s independent reading books to see what types of families were represented and identify those that were missing. They found the majority of books included families with a mom and a dad—while other family structures weren’t equally represented.

Students created a class "Family" book with a page from each student showing what their family looks like. The class discussed representation and fairness, and what it means to not see yourself reflected in books and media.

“We talked about that with students and they felt like it wasn’t fair that all types of families weren’t equally represented,” Lefkowitz says. “So over the course of three years, we've really tried to revamp and change the books that we're reading to make sure that they reflected the kids in our class and the world around them.”

For Jacqueline Adam-Taylor (Greater Philadelphia ‘07), a principal of the High School of Commerce, working with Executive Principal Paul Neal, in Springfield, Massachusetts, continuously reassessing the school’s curriculum is an important part of dismantling systems that may perpetuate racism in the classroom.

When reviewing this year’s school’s curriculum, Jaqueline and her colleagues set out to address a number of obstacles standing in the way of the school’s anti-racist work, including inconsistencies in how the curriculum is taught. Not every student in the school was receiving the same access to high-quality curricula, which was worrisome to Adam-Taylor and her fellow school leaders.

“We realized that all of our teachers have a lot of discretionary space around the curriculum, and that actually continues to reverberate racism, or bias, or just non-alignment for all of our students,” she explains. “For this upcoming year, we've already done a three-day PD [professional development], where all teachers understand where we are, what we’re doing, and that our school is based in inequity, so we need to push ourselves as a whole to do anti-racist work.”

Her school also made the decision to shift to Facing History and Ourselves, a curriculum that uses lessons of history to explore racism and prejudice and challenges teachers and their students to stand up to bigotry and hate. In one of the curriculum’s units, Choices in Little Rock, students are taught about the choices that politicians, members of the media, students, and communities made during the efforts to desegregate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957. Students learn the importance of civic action and individual choice in building a just democracy.

“We’re making sure that our history curriculum becomes more thematic versus chronological,” Adam-Taylor says. “For example, making sure themes of suffrage are multifaceted, so that students are able to feel different parts of it from different perspectives and from different parts of the world.”

Balancing Multiple Perspectives

Introducing students to a breadth of perspectives helps them build a more complete view of the world. That includes building students’ understanding of the systems of power that have worked to uphold racism throughout history. But it also means balancing these narratives with stories of the strengths, gifts, and resilience of those who have experienced oppression.

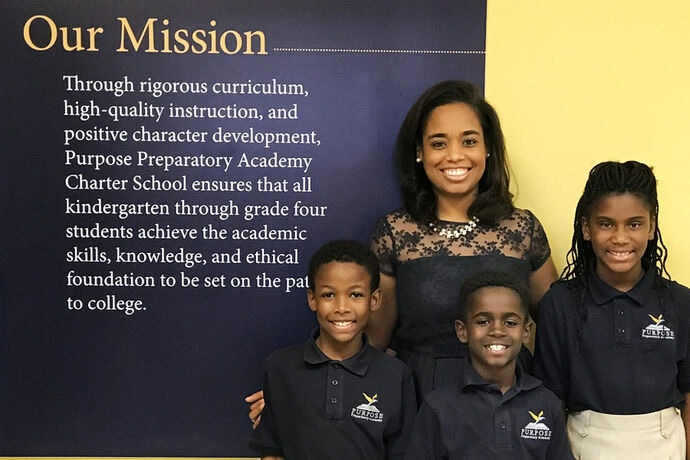

At Purpose Prep Academy, a K-4 school that serves a majority Black student population in North Nashville, Tennessee, the school team set up working groups with students and families on how to best center their experiences through a historically comprehensive and asset-based lens. They took a critical look at the school’s social studies content and saw an opportunity to expand students’ understanding of Black history—beyond slavery and the Civil Rights movement.

Lagra Newman (Los Angeles ‘05) is the founder and head of school at Purpose Prep and says that while it’s important for students to build their knowledge of the role that racism and oppression have played throughout Black history in the United States, students—especially those in younger grades—should not be learning about people from Africa for the first time through the context of slavery.

“It is unjust for students to learn their history starting in 1619, especially from the viewpoint of how they were viewed by society at that time,” Newman says. “And then to go back and try and reconstruct their humanity in that learning.”

Before school started last year, teachers immersed themselves in learning about Africa and expanded their knowledge of the continent’s rich history and culture. Now, students learn about Africa’s complex diaspora, culture, history, starting in kindergarten. They build context around African countries and understand the continent’s role as a global leader of commerce, art, and intellectual contributions. This context helps students build a deeper understanding of the complicated history around colonialism and slavery in subsequent grades.

“I think it shifts the conversation and allows students to be really critical of those systems of oppression only after developing a really strong foundation of self, which is so critical for all children,” Newman says. “We have to be very intentional to support Black children to get that foundation.”

At the same time, Newman notes that decentering white colonial narratives does not mean removing those perspectives entirely.

“With anything, we want to expose students to multiple perspectives—that’s an important part of our framework,” Newman says. “So it's not void of the perspective of the colonizers, because students need to know that, too. But I think the problem is when you don't have an Indigenous perspective and only the colonizers, you're not able to critically reflect on the damage that was done, what was lost, what was gained—that type of critical thinking is not available to you.”

Shauna Russell is the director of academics at Purpose Prep and helped lead the revisions to the school’s social studies curriculum. She notes that being critical of dominant perspectives not only gives students a more complete, nuanced understanding of the world as it's currently constructed. It helps them develop their agency and their voice so they can become active participants in the world.

“Students need to be able to speak the language of the systems around them in a context that gives them the skills, knowledge, and confidence to deconstruct them as they grow,” Russell says.

Beyond Booklists - Decolonizing Learning

What students are learning—the perspectives and points of view—makes a difference in shaping their worldview. But so does the way they learn. And not all students have equitable access to authentic learning opportunities that promote identity development, experimenting, and creating.

“Disproportionately our Black and brown students who are attending low-income schools are getting access to curriculum that is very procedural, as opposed to problem-solving and application-based,” says Priti Johari.

Johari, a 2002 Bay Area alum, is the chief academic officer at the Academy of the Pacific Rim (APR) in Boston, a school that serves a majority Black and Latinx student population in the fifth through 12th grades. As part of her school’s anti-racist work, she is helping the school adopt a framework for “deeper learning.” The model is based on the idea that students who engage in complex critical thinking and decision making develop skills that are required for leadership roles, versus learning that prioritizes following procedures and compliance.

Students at APR have more opportunities to work in small groups and engage in seminar-style discussions across subject areas. They consider different points of view, build on previous knowledge, come up with solutions, and incorporate feedback. Often this kind of learning happens through circles, which puts everyone in the classroom on equal footing.

“If you're not building brainpower, then you're not actually doing the anti-racist work,” Johari continues. “So anti-racist education isn't just about building good relationships and us being able to get along. Our work as teachers, as educators, is really to empower our students to be both problem spotters and problem solvers.”

The Importance of Identity Work for Students

Identity work is an important part of helping students unpack the complexity of different identities and create meaningful dialogue across lines of difference and power in the classroom. School leaders noted that embedding racial identity work into their curriculum and learning experiences means students build self-confidence about their own identities, deconstruct false racist notions of what it means to be a Black, Indigenous, or person of color, and gain language and skills for having courageous conversations about power, privilege, and oppression.

Karima Wilson (Houston ‘03), a former school principal, is the founder and CEO of Forged Ed, an organization that provides equity training in K-12 schools. She found that many school leaders are looking for ways to structure meaningful identity work and integrate it into students’ overall learning. Over the past year, she piloted an advisory curriculum focused on identity development in two schools, one in Houston, and one in New York City. Students learn about their own ethnicity and heritage and that of their classmates through discussion, family interviews, and journaling. Wilson explains that students of color often receive conflicting societal messages about who they are and who they can become. This identity work builds students’ resilience when they are confronted with racist stereotypes, and also helps them deepen their sense of belonging in school.

“Sometimes the experience for students of color in schools has been that you can be smart or be a member of your ethnic group,” but you can’t be both simultaneously, Wilson says. “And part of bringing conversations of identity into the classroom is to also say, what are all of the ways that my identity can show up? It's about helping students to think reflectively about their identity and helping them to see, what does it mean to be a scholar in my skin?”

At Purpose Prep Academy, students participate in “Identity Days,” an idea that came out of a parent working group after parents expressed concerns about school uniforms limiting students’ cultural self-expression. Identity Days offer a purposeful way for students to celebrate their cultures and communities. Before the COVID-19 pandemic temporarily halted the practice, students would come to school dressed in ancestral attire, or as future doctors, musicians, or people from history. Students gathered in the multi-purpose room to present their attire and share their stories.

Affirming identities isn’t just about children celebrating culture and learning about each other. This work builds resiliency that students can tap into in the future when confronting complex situations, such as being one of the few Black students in a predominantly white school, which some Purpose Prep students experience when they go on to middle school.

“There's that confidence that they have in themselves in their intelligence and who they are and what they know, what they're capable of,” Newman says. “And that is priceless. And I believe that if you can build that foundation for children, it allows them to be able to navigate different systems and not be oppressed by them.”

Identity Work Matters for Educators Too

Sharon Michaels (D.C. Region ‘13) is passionate about identity development work which is important for both students and teachers. Michaels is an assistant principal in Washington, D.C. She’s also the founder of labfourseven, an organization that provides educators with anti-racism resources, and is a doctoral student studying organizational learning.

In addition to these roles, for the past two summers, she’s partnered with the National Museum of African American History and Culture, designing and co-facilitating a week-long in-person workshop for educators to learn how to talk about race, and racism in the classroom. Much of the work starts with educators holding up the mirror, looking inward at their identities, beliefs, and biases, and how these manifest in the classroom.

Drawing from several frameworks such as Glenn Singleton's Courageous Conversation protocol for race talk, participants explore how different aspects of their identity impact their role as educators, such as race, gender, sexual orientation, and ability. Educators then put their knowledge into practice and model how to have conversations about race, racism, and identity with students, and how to interject and interrupt systems of oppression whether they occur in the classroom, among staff, and in other contexts.

"If teachers understand who they are, they are able to then lead these conversations with students who may not share their backgrounds,” Michaels says. “We focus on what it means to listen deeply, to be self-aware, and to understand the role your identity plays in every interaction with students.”

Educators gain practical skills for the classroom and also learn about tools for working with different stakeholders to move antibias anti-racist work forward in their schools and organizations, such as changing curriculum, cultural norms, and policies.

“So much of anti-racist work happens through a decision-making lens,” Michaels says. “When we talk about moving from the people who initiate the conversation to the people who are impacted by the conversation, we also have to think about who holds power, and how to engage all the people in between.”

Developing Students into Change Makers

When students have access to a curriculum that helps them unpack the inequitable systems that shape their school and the world around them—and to see a representation of themselves as powerful changemakers—they are able to find their voice and become advocates for themselves and others.

At the Academy of the Pacific Rim, social responsibility and “kaizen,” a Japanese term meaning "continuous improvement,” is baked into students’ learning. Students participate in learning circles when discussing complex social issues, as a way to equitably share the power and voices in the classroom.

After a video of a student using sexist and racist language circulated on social media, Johari recalls that students from The Academy’s LGBTQ+ student group took the initiative to address the issue with their fellow students directly. They organized restorative circles by grade level during their advisory session to talk about what happened, hear people’s experiences, and offer training on how to be an effective bystander.

“Students are learning to use the systems we’re building in the classroom to also problem-solve the things that are happening in our community,” Johari says.

In the wake of the George Floyd protests, the leadership team at The High School of Commerce is focusing on the legacy of the protests. That’s why Jaqueline’s Executive Principal, Paul Neal is pushing to create an activism class for the next academic year.

“The Executive Principal, Paul Neal really thought about what we are going to do for our students and how we create systems within our school to make sure this work stays front and center,” she explains.

They’re looking at the social justice standards from Teaching Tolerance—which help educators to engage in a range of anti-bias, multicultural, and social justice issues in the classroom—as a potential framework for the class.

“Basically, each year there's a project building onto their activism work, so that students understand the language and what it takes to disrupt systems as early as ninth grade,” says Jaqueline. “We hope this activism class will help them be more invested in school as well.”

Young students at Purpose Prep also gain language and tools for speaking out through a variety of powerful experiences. After students learned about the history of voting in the United States, the school launched a social media campaign encouraging parents to bring their children to the polling place and snap a photo. Families and staff helped raise funds for the Flint water crisis and took a field trip to learn from the community about the injustices surrounding access to clean water. During a unit on Black history, students learned about Claudette Colvin, who at 15-years-old was the first Black person to refuse to give up her seat and move to the back of the bus during the Civil Rights movement, nine months prior to Rosa Parks.

These experiences are formative for young learners. Students see that they can make a difference in the world even as children. They learn the value of building community and gain lifelong habits around social responsibility.

“Exposing them to those examples and empowering them lets them know that they are important and their voice matters and that they can take action immediately,” Newman says.

“All of that serves to get that empowering beyond the academics, that empowerment that they need to continue to think about their community obligation and how they have to continue to push our nation to be better.”

Examining learning through an anti-racist lens means continually questioning and revisiting policies and practices over the long haul. This includes what and how students are learning in the classroom, as well as the structures and systems that make up the school environment as a whole. At S.T.A.R. Academy, Friedman and her team know this work is a marathon and lives in the everyday actions of teachers and staff as well as the long term vision for the school.

"Anti-racism is a lens you bring to all your decisions as an educator, it does not just live in the curriculum," Friedman says. "For us, it's an ongoing commitment to investigating our practices and policies, and interactions with students and staff."

Resources on Anti-Racist Education

This story includes just a small number of the countless educators across the Teach For America network and beyond who have for years pursued a focus on anti-racism work in schools. Teach For America strives to train our teachers to be anti-racist educators. This work is part of an ongoing evolution and much work remains to be done. This following list of resources is not all-inclusive but meant to offer a few examples for further learning and exploration.

- How to Be an Antiracist Educator from ASCD. Includes tips and activities from educators.

- Center for the Study of Social Policy: Using an Anti-Racist Intersectional Frame at CSSP

- Everyday Antiracism, Mica Pollock (2008)

- Culturally Responsive Teaching and The Brain, Zaretta Hammond (2014)

- Let’s Talk! Discussing Race, Racism, and Other Difficult Topics With Students a guide from Teaching Tolerance

- The Urgent Need for Anti-Racist Education from Education Week

- Resources for Talking About Race, Racism, Racialized Violence with Kids from the Center for Racial Justice in Education

- Why Teaching Black Lives Matter Matters | Part I from Teaching Tolerance

- Teaching Resources for Black Lives Matter School Week of Action from D.C. Area Educators for Social Justice

- Addressing Race and Trauma in the Classroom by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network

- Educators Tackle Tough Conversations about Race and Violence - This Time Virtually - from Chalkbeat

- The Coretta Scott King Book Award Winners- Award-winning books by African-American authors and illustrators that demonstrate appreciation for African-American culture and universal human values.

- Coalition of Anti-Racist Biology Teachers Facebook group moderated by alumna Natalie Cross

Read more about how school leaders are reassessing policies around hair and dress codes, conduct, and hiring as they commit to the work of building an anti-racist school culture. And share your thoughts on this story or suggest other stories for us to pursue.

Sign up to receive articles like this in your inbox!

Thanks for signing up!

Content is loading...