Can We Get School Right for Our Youngest Learners?

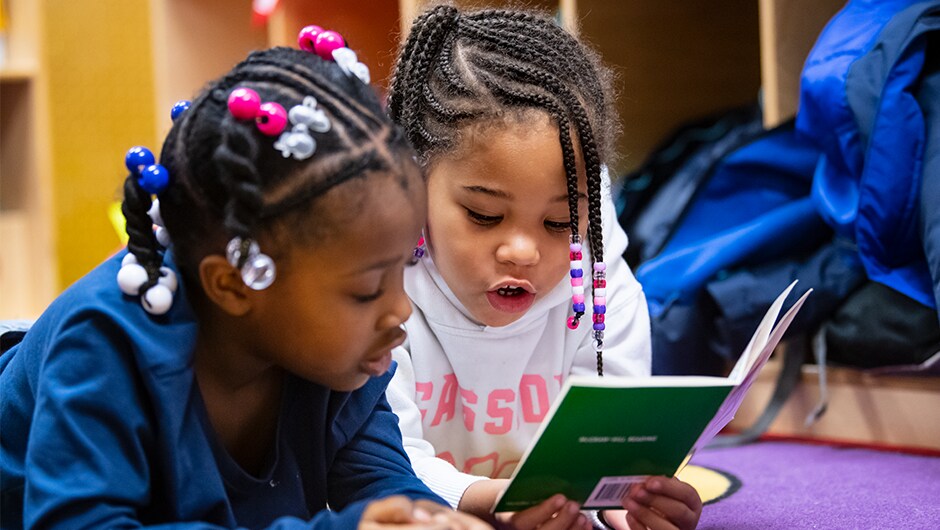

In cities and states around the country, Teach For America alumni are building and leading the systems to nurture our nation’s youngest learners. Here’s a look at five places showing what’s possible.

Not everything in American politics is divisive. Most of us, it seems, are willing to invest in little kids. In a fall 2018 national opinion poll conducted by the Center for American Progress, more than two-thirds of registered voters agreed that public financing of child care and early learning is good public policy.

Many politicians were a step ahead of the findings. In the November 2018 elections, no fewer than 15 elected or re-elected governors won in part on their promises to expand early education—often framed as beginning at birth—not only in liberal strongholds like California and Minnesota, but in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Colorado, even Kansas. Big city mayors have proven that pre-K expansion is a winning issue, too; see New York and Chicago.

Sara Mickelson (Houston ’09) is the chief of staff in Oregon’s department of early learning, overseeing the state’s policy and legislative work to expand infant, toddler, and preschool programs. “When we say the early childhood period makes the biggest difference in a person’s life,” she says, “we’re selling a big promise.” It’s a guarantee to taxpayers that that the financial investment will pay dividends down the road in successful, engaged adults. But it’s also an assurance to kids and their parents, she says, that no matter what happens down the road, their young lives are valuable right now and they deserve to thrive.

Now, educators and policymakers are the ones tasked with keeping those promises and capitalizing on the political glow. To do it, they need to wade through early childhood education’s fragmented landscape and untangle decades of decisions made before the youngest children became a public priority. For example, certification standards for early educators vary significantly. In part because of that, compensation can be as low as minimum wage, or on par with K-12 teachers. There’s little in the way of professional development, stifling pathways to leadership positions. And systems designed to measure the quality of early childhood programs are relatively new. The people behind them are still figuring out what variables matter.

In cities and states across the U.S., Teach For America alumni are in positions to lead and influence efforts to get new policies and practices in place, and many are writing their job descriptions as they go. They have a big chance. Can they get it right?

We asked alumni in five parts of the country to tell us how they’re designing systems to benefit the youngest learners, and who’s working alongside them. Stop one is San Antonio, Texas.

San Antonio

Raising the bar citywide

In 2012, San Antonio's then-mayor Julián Castro led a massive campaign to fund pre-K expansion through a sales tax increase. He sold it as an investment in the city’s future workforce, secured the support of the business community, and brought the idea to a citywide referendum. It passed and Pre-K 4 SA was born.

Today, Pre-K 4 SA operates four no- or low-fee schools serving 2,000 4-year-old students in state-of-the-art “demonstration” sites. Children play and learn in classrooms designed to promote brain development, social skills, and foundational academic thinking. Teachers earn salaries nearly unmatched in the field: between about $58,000 and $80,000.

Almost perfect, right? But Larrisa Wilkinson (D.C. Region ’06), Pre-K 4 SA’s director of professional learning and program innovation, says serving 2,000 kids isn’t ambitious enough. “It’s about raising quality for the whole city,” she says.

The city of San Antonio has 15 public school districts. Most of them provide half- or full-day pre-K funded largely with state dollars, but there are not enough seats to serve every 4-year-old. When Pre-K 4 SA launched, about half of the districts opted to partner with the initiative on the promise that a certain number of seats at the Pre-K 4 SA sites would be reserved for their students—a win for superintendents hoping to enroll as many kindergarten-ready kids as possible. In exchange, the districts pay per-pupil funding to Pre-K 4 SA.

The money Pre-K 4 SA takes in—from districts, tax dollars, and philanthropy—goes in part to provide various levels of professional development. That includes a series of free classes and conferences open to any teacher in the city. Winter/spring sessions this year include a course on teaching STEM with outdoor materials and another on student storytelling through speech and drawing.

The organization also awards $4.3 million in grants to partner districts and to 50 early childhood centers throughout the city. Wilkinson designed the grants so that partners would address foundational costs first, like credentialing staff or moving from half-day to full-day programs. Once the foundations are in place, grants can be used for higher-level needs, like purchasing curriculum or building outdoor classroom space.

Pre-K 4 SA also partners closely with districts to provide training, including intensive trainings for principals at schools with pre-kindergarten classrooms—because in San Antonio, as in most places, many principals became leaders before their schools started teaching 4-year-olds. (In the past few years, states such as Texas and Illinois have started requiring principal prep programs to teach early childhood practices.)

“We have a lot of leaders who don’t understand early childhood, and want and need to,” Wilkinson says. “The game changer is in leadership.”

Atlanta

Aligning early childcare with school

As Atlanta Public Schools’ first director of early learning, Sydney Ahearn (Chi–NWI ’08) and her team oversee what happens among the 1,100 4- and 5-year-old students in the district’s 54 pre-K classrooms. But since stepping into that role in 2016, she has spent much of her energy on improving partnerships with early child care providers, who watch over children as young as infants.

As in most cities, Atlanta’s array of child care providers exists in a separate regulatory domain from the school district. Some are excellent, others less so. “We see [our schools] as the customer of the 0-5 providers,” Ahearn says. “Most of those kids will come to us. So if we partner with providers and get better about alignment, that benefits our district as a whole.”

That support has looked like a mini-grant program started in 2018 for child care providers, funded through a partnership with the United Way, to better support kids’ transitions to kindergarten. Some providers used the funds to engage with families, others to purchase curricula. Ahearn’s team also worked with the Georgia Early Education Alliance for Ready Students to launch the Atlanta Early Education Ambassadors program. Through it, cohorts of parents and community members become champions for early education in their communities and help link up families, child care operations, and schools.

Atlanta Public Schools (APS) also partners with the YMCA of Metro Atlanta, which operates many Head Start classrooms. In addition, the YMCA provides supports such as health care and mental health services in 28 APS pre-K classrooms, funded with Head Start money.

The YMCA and the school district have been partners for nearly 20 years, but once APS created Ahearn’s role, the district had more capacity to capitalize on the YMCA’s long experience in underserved communities. Ahearn was able to deepen the organizational synergy with the help of the YMCA of Metro Atlanta’s Robyn Tedder (Metro Atlanta ’09).

Tedder launched the pre-K program at Atlanta’s Purpose Built Schools before becoming the YMCA’s senior director of community partnerships and signature programs. In her newly created role, she’s charged with expanding partnerships and increasing access to the YMCA’s early learning programs.

The women have become colleagues and friends. While on work calls or catching a gym class together, Tedder and Ahearn talk through projects like the first unified-enrollment system for the YMCA and Atlanta Public Schools. Ahearn taps Tedder for advice on improving APS Head Start sites. And as the YMCA completes construction of a state-of-the-art early child care center on Atlanta’s west side, Tedder consults Ahearn on how to strengthen alignment between the center and nearby schools.

Creating a seamless continuum of early child care providers and school systems brings up all sorts of challenges. They operate on different calendars. There’s often a large pay differential between teachers in the different settings. Principals and center directors often operate from different sources of knowledge with different visions of excellence. But Ahearn hopes stronger relationships will drive progress.

“We can break through those barriers,” she says, “and get to real innovation.”

Louisiana

Raising pay

At the age when babies’ and toddlers’ brains are developing faster than at any other time in their lives, the people we trust to teach them often earn barely more than minimum wage.

“That’s definitely true,” says Laura Bornfreund, the director of early and elementary education policy at the New America Foundation, a national think tank. But in a handful of places, she says, policymakers are inching toward raising pay.

In Louisiana, median hourly wages paid to early childhood caregivers are some of the lowest in the nation—barely $9 per hour. In 2007, the state passed legislation to boost pay with a refundable tax credit—one of the first in the nation—for caregivers at centers that receive public funding (often tied to serving students from low-income communities). In 2017, the Louisiana Department of Education’s early childhood policy team, led in part by Teach For America alums Nasha Patel (S. Louisiana ’10), Erin Carroll (San Antonio ’10), and Taylor Dunn (G.N.O. ’11) made revisions to the credit to align it more closely with improving quality.

Turnover among Louisiana’s early childhood caregivers is about 40 percent a year. So these policymakers helped to reshape the credit to incentivize caregivers to stay in their jobs, and their professions, for longer. A first-year caregiver with a Child Development Associate (CDA) credential can claim a $1,630 credit. At tax time one year later, the credit is worth about $2,500. Two years later, it caps out at about $3,300—nearly 20 percent of the median annual salary. Caregivers can also bump up their credits by earning the state’s new early childhood teaching certificate—a move to improve the quality of the workforce.

Publicly funded child care centers are eligible for tax credits too, which can be passed on to caregivers in the form of pay bonuses or professional learning. Under the 2017 policy tweaks, a center can earn a bigger tax credit if it does well according to the state’s quality rating and improvement system, launched in 2015. The better a center scores on quality, the higher its credit—up to $1,500 for each student enrolled.

“It will take more and increased public investment to really solve the problem” of paying a fair and attractive wage to people who care for and teach young children, says Bornfreund. But Louisiana’s tax credit is a starting solution, and one that other places could replicate.

New York City

Reorganizing city resources to prioritize kids and early childhood providers

Under New York City’s mayor, the school system’s highest-profile win has been to open free, citywide pre-K classrooms to nearly 70,000 4-year-olds. And now, over the next three years, New York City’s Department of Education (DOE) aims to expand “3-K” to 60,000 3-year-olds.

But while Pre-K for All steals the headlines, a separate effort to improve quality and accessibility is quietly moving forward despite significant complexities. The DOE is painstakingly assuming responsibility for 370 early learning centers—many of them Head Start providers—and a vast network of smaller child care centers. All currently fall under the Administration for Child Services, the city’s child welfare division. The centers, which operate with federal funds reserved for students with the highest level of financial need, serve children as young as newborns and as old as 5.

While the transfer could sound like a bureaucratic paper shuffle, the creative effort is enormous, and the promise for young kids and families is huge, says Xanthe Jory (N.Y. ’96), the chief policy and planning officer for the DOE’s early childhood division.

From an educational standpoint, Jory says, the DOE has capacity and resources to provide professional development for teachers and center directors and to set and hold high standards for quality throughout the birth-to-5 system. With streamlined enrollment and record-keeping, the transfer will also spare families and providers much complicated, redundant paperwork.

In the longer term, the DOE is working to develop strategies for all early childhood programs to serve more students in socioeconomically integrated settings—a small step toward addressing the segregation that infects the entire school district. Currently, many of the centers operate in racially segregated, predominantly low-income neighborhoods.

The DOE is also considering the potential for moving toward more equal pay for early childhood teachers. Under current constraints, many have earned little more than minimum wage. As the system grows, and as funding streams are blended, money could be freed for center-based teachers to get raises. It’s a critical issue, Jory says, and “very much on our radar.”

Chicago

Closing the opportunity gap for infants and toddlers

Since outgoing Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel took office in late 2011, the number of seats in public, full-day pre-K programs has increased by 80 percent to roughly 18,000. By 2021 Chicago aims to have enough seats (about 24,000) to enroll every 4-year-old. A Teach For America alum and former elementary school principal, Michael Abello (Chi–NWI ’08), was recently appointed to lead the expansion as Chicago’s chief of early childhood education.

While Abello focuses on students ages 4 and up, Jesse Ilhardt (Chi–NWI ’08) and Kelly Lambrinatos (St. Louis ’07), co-founders of VOCEL, are working to develop a new learning paradigm for kids from birth to age 3 and their families.

VOCEL, which stands for “Viewing Our Children as Emerging Leaders,” launched in 2014 as a full-day, low- or no-cost preschool that shared space with a parochial middle school on Chicago’s West Side. But as the city opened up pre-K seats at district schools, Ilhardt and Lambrinatos made a pivot.

They looked around the city and saw ample enrichments in higher-income neighborhoods for parents and toddlers: music classes, baby yoga, support groups. “But they were completely out of reach for most of our families,” says Ilhardt, who serves as VOCEL’s director of programs.

So they worked with parents and their board to design a free, yearlong, once-a-week program where the youngest kids and their primary caregivers—typically parents—come together for a two-hour session. In the first hour, children and caregivers work and play together through rigorous enrichment activities. In the second hour, the caregivers split off to learn, for example, what child development research says about how to respond to meltdowns.

“We wanted to see the parent and child truly as equal clients, with equal attention given to curriculum and program design for them both,” Ilhardt says.

Ilhardt and Lambrinatos pitched principals on their idea: Give us space in your schools to run our programming, and in return, we’ll give you better-prepared students, plus engaged and empowered parents. Michael Abello, before he took the district job, was one of VOCEL’s first principal partners.

This school year, VOCEL’s child-parent academy is serving 75 families at eight school sites, with plans to expand to 15 sites in 2019-20. After completing the program, nearly 90 percent of parents felt they had more support from other parents, and all said they had gained knowledge of their children’s language and social-emotional development.

Elda Alcaraz attends VOCEL with her 2-year-old son, Giovanni. He’s become a chatterbox since attending the classes, she says. And the parent classes and support network have helped her to shift her parenting strategies toward more patience. The biggest gift is the uninterrupted time together to play, she says. “I see that he likes it, and I like it too.”

Sign up to receive articles like this in your inbox!

Thanks for signing up!

Content is loading...