I Won’t Deny My Students Books

A national School Librarian of the Year and reading activist writes about how book bans harm children.

Many school librarians and teachers are scared and frustrated—and they have ample reason to be.

As calls for book bans spread across the nation, they worry that championing diverse books will cost them their jobs. Out of fear, some librarians have removed books from shelves even before a formal review has taken place. These must have been extremely painful decisions. Librarians don’t want to take books away from youth that are crucial to their understanding of the world and themselves.

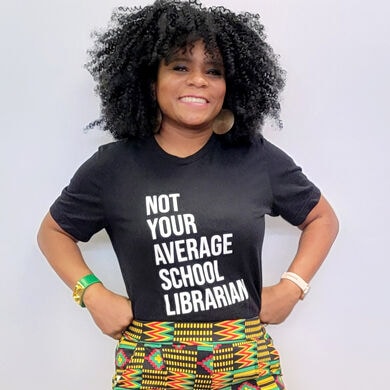

While I fully understand this conundrum, I simply won't deny my students books. As a school librarian for six years and the 2020 national School Librarian of the Year, I know what children need to see in books—and I know it's my job to give them access to those books.

Moreover, I am a Black woman with Black children and many of the books being banned are about Black history. Banning books that tell the truth about Black history is telling Black children—telling my children—that they don’t matter. And, as an ally and educator of LGBTQ+ students, I will not hide books about them either. They are watching and they deserve representation.

Although book bans are nothing new, they have grown far more common recently. I remember hearing about a book ban once a year; it was a rare, isolated occurrence. Now, it is a topic of everyday conversation. The American Library Association tracked 729 book challenges in 2021—which typically sees about 500 challenges a year. (A challenge is an attempt to remove or restrict materials, while a ban would remove them.)

“Banning books that tell the truth about Black history is telling Black children—telling my children—that they don’t matter.”

Politicians and parents advocating for book bans say they are meant to protect parents’ rights and ultimately children—but they do the exact opposite. Within children’s literature, it is widely known that books provide youth with “mirrors and windows.” The phrase, introduced by educator Emily Style and expanded upon by multicultural children’s literature researcher Rudine Sims Bishop, conveys the idea that books allow children to see themselves in literature and also look into the lives of others. Books also provide “sliding glass doors,” according to Bishop, which empower readers to walk into a story and become part of the world created by the author. Without access to stories that reflect their identity and the identity and cultures of others, it’s harder for many youth to discover and take pride in who they are and have empathy for others.

It is traumatizing to constantly feel alone—and can even be deadly. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for children ages 10 to 14 and LGBTQ youth are four times more likely to consider, plan or attempt suicide. What messages are we sending to youth when most of the books targeted in 2021 are about Black and LGBTQ+ people?

These challenges and bans are undoing recent progress in expanding access to—and interest in—diverse books and more comprehensive histories. Many educators had been making great strides in promoting diverse books in their classrooms and libraries—particularly during the recent movement for racial justice. After George Floyd's murder by police officer Derek Chauvin in 2020 and the civil rights marches that ensued, books about racism by Black authors saw an uptick in sales. Never in my career as an educator had I received so many calls, emails, and DMs from family, friends, and colleagues asking for book recommendations so they could broaden their knowledge.

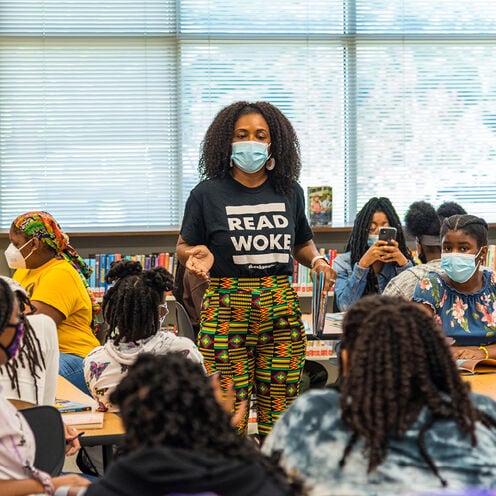

During this time I found myself feeling hopeful. I poured more energy into Read Woke, a reading challenge I started in 2017 in response to shootings of unarmed Black people, the lack of diversity in children’s literature, and the repeal of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (which the Supreme Court later blocked). I started the Read Woke program for students at Meadowcreek High School in Norcross, Georgia, where I am a media specialist—inviting them to read books that challenged the social norm, gave voice to the silenced, and inspired action. As word spread, other educators began implementing Read Woke in their schools. The program is now in over 29 states and three countries.

Widespread book challenges and bans threaten to undo all of the hard work that I have done alongside my students, fellow educators, and authors. Many of these campaigns are local efforts led by parents. But chillingly, many more are now coming from the state level, part of a wider web of legislation designed to restrict discussion of racism, sexuality and gender identity in schools. These campaigns have been used by politicians to stoke fear and anger in their base and drive people to the voting booth.

Get more articles like this delivered to your inbox.

The monthly ‘One Day Today’ newsletter features our top stories, delivered straight to your in-box.

Content is loading...

The material about American history often specifically targeted in recent state legislation is “The 1619 Project,” a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalism initiative by The New York Times Magazine examining how slavery shaped America. The project was published as a book last fall. According to PEN America, a nonprofit that defends free expression, 23 bills in 15 states have been drafted across the country since January 2021 that would prohibit teaching The 1619 Project in the classroom. While several bills are still pending, schools in one state are banned by law from requiring an understanding of the project and a board of education rule in another state bars teachers from using project material in classroom instruction.

Many other bills and laws work to target racial and LGBTQ+ topics more generally, including bills that would empower parents to have books about sex and sexuality removed from school libraries. A bill recently signed into law expedites the process for removing books considered "harmful" from school libraries, placing the final responsibility on school boards. Laws like these, in essence, override the training librarians have to curate collections they know will reflect and support all of their readers in an age-appropriate way.

While it won’t be easy to undo the damage, there are so many ways we all can fight back against this assault on intellectual freedom, education, and the safety of children. You can donate to nonprofits that fight against censorship, start community book clubs, start a family book club, write to your local legislators, vote, and email your children’s school and ask what is being done to promote diversity.

A recent CBS News/YouGov poll report shows that a majority of Americans don’t agree with the idea of banning books about history or race. And there is a growing movement to push back against these bans. But we all must act. With ignorance and fear so loud, now is the time to send messages of unity and hope. Protecting our freedom—and that of our children—is up to us.

We want to hear your opinions! To submit an idea for an Opinion piece or offer feedback on this story, visit our Suggestion Box.

The opinions expressed in this piece, and all others in our Opinion section, represent those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the Teach For America organization.

Sign up to receive articles like this in your inbox!

Thanks for signing up!

Content is loading...