What Learning Can Look Like in the Wake of Disaster

A network of educators in Eastern North Carolina is responding to devastating floods by ensuring kids have what it takes to rebuild.

Before the rains came, seventh grader Ni’zavion Black spent Saturday afternoon, October 8, playing basketball.

The drizzle started around 4 p.m., as he was expecting. His science class had been tracking Hurricane Matthew’s path to their homes in Tarboro, a town of about 11,000 people in the lowlands of Eastern North Carolina. He trotted home to the one-story brick house where he lives with his grandparents.

As the drizzle turned to a downpour, his grandmother packed up belongings and placed them on high shelves to escape possible flooding like the kind that destroyed her home following Hurricane Floyd in 1999. Around dinnertime the electricity cut out, but Ni’zavion was too nervous to have much of an appetite, anyway. As the rain beat down and the wind reached speeds of 75 miles per hour, the family huddled in the hallway with a candle and a flashlight, watching the news on Ni’zavion’s cell phone. By midnight, the worst was over and Ni’zavion was sent to bed, but he didn’t sleep well.

On Sunday morning, the residents of Tarboro woke up to blue skies and less damage than many had feared. But about a half mile south of Ni’zavion’s home, the Tar River was rising. Soon his whole neighborhood would be standing in a murky sea.

When disaster strikes, good people rush in to help—college students, faith groups, retirees, veterans. And in Tarboro, as elsewhere, some of the first and most critical responders were local educators. The floods following Hurricane Matthew affected about 1,000 homes in the Tarboro area, including hundreds of children. In response, their teachers and school leaders helped lead a remarkable community-wide effort to provide basic services like food, shelter, and fellowship.

But the action that may have the greatest impact on the flood recovery is one that began before any rain fell, and will continue long after families are resettled. With the support of a superintendent willing to rethink schooling, principals in Edgecombe County, including three Teach For America alumni, had already started to reconfigure their schools to put a focus on nurturing students to become the leaders their communities need.

Now, in partnership with others, they are using the terrible opportunity created by the hurricane to help their students lead efforts to help one another. And as the students help one another, they’re learning the habits of leadership they can channel into revitalizing their town.

As flood waters rose, schools superintendent John Farrelly was planning for the worst. W.A. Pattillo Middle School, down the street from Ni’zavion’s house, was at risk of flooding. Nearby, Princeville Elementary would almost certainly go under.

Princeville, home to about 2,000 people, is lower than Tarboro, topographically. It celebrates its history as the oldest town in the nation incorporated by black Americans, tracing its founding to the end of the Civil War in 1865. But it was built on land unused and unwanted by the white ruling class—one of the nation’s earliest examples of real estate redlining. After Hurricane Floyd, Princeville was completely submerged. Residents rebuilt, assured that floods so devastating could only occur once every 500 years.

Farrelly arrived in Edgecombe County in 2011 with a reputation as a superintendent willing to take a hammer to broken systems. In his previous post in nearby Washington County, he brought in Teach For America, whose corps members and alumni he credits with helping turn around the county’s high school, which had been one of the lowest-performing in the state.

In Edgecombe, Farrelly’s priority has been hiring talented leaders. Forty percent of his school leaders have come through a nationally renowned principal training program called the Northeast Leadership Academy, or NELA. Fourteen Teach For America alumni are graduates. Nine are now principals in the region, three are assistant principals, and one, Erin Swanson (E.N.C. ’02), works for Farrelly as his director of innovation, tasked with creating conditions in Edgecombe County schools for students to become leaders.

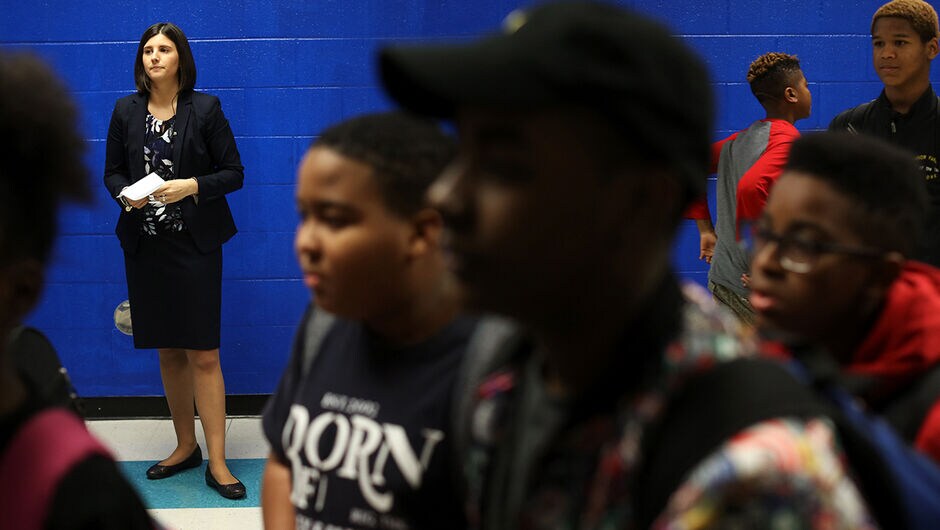

Following the flood, Farrelly was counting on his principals to take charge. One of them is Ni’zavion’s no-nonsense principal Lauren Lampron (E.N.C. ’10), a NELA graduate in her third year at Pattillo and her second as its leader. As flood waters threatened her school on Sunday, Lampron and her staff joined district colleagues to move items from the first floor of the school to the second. On Monday, while Lampron visited emergency shelters, her husband assisted the district’s maintenance department stacking sandbags around Pattillo’s entryways. The school, which had to be completely rebuilt after Hurricane Floyd, sits on a plot of land higher than most of the neighborhood. When the floodwaters finally peaked, Pattillo stood dry, as if on an island, while nearby homes, like Ni’zavion’s, were swamped.

Ninety-three Pattillo students out of 270 were displaced. Princeville Elementary and nearly all of its students’ homes were again underwater. Over the weekend following the hurricane, two schools became shelters and others, including Pattillo, opened distribution centers for food, clothing, and other supplies. Many students moved into the shelters, while others stayed with relatives or in hotels as far away as Greenville, 25 miles south.

Overnight, principals like Lampron went from school leaders to school leaders plus emergency managers. They logged 20-hour days at the shelters. They worked with staff to create spreadsheets tracking their students’ whereabouts so they could determine everything from new bus routes to who needed blankets or a warm coat. They stayed in touch with parents whose stress levels were rising as nights in cramped quarters dragged on. Lampron couldn’t get those families off her mind.

“Usually, we’re the problem solvers. But this is an experience where we don’t have all the answers,” she says. “When we’re talking about something affecting a large majority of the school, it makes even the adults feel powerless.”

Lampron relied on her network to help, everyone from her assistant principal and instructional coach to an old friend from Teach For America, Daniel Riley (E.N.C. ’05). Riley’s official title with the organization—Twin Counties leadership coach (encompassing Edgecombe and neighboring Nash County)—doesn’t capture the extent of his work to build up his adopted home. Beyond coaching teachers, he meets with administrators, board members, entrepreneurs and anyone with an interest in schools and kids. He’s a consummate connector—introducing, for example, a sheriff’s deputy who works as a school resource officer to a corps member concerned about discipline practices at the high school. He speaks at churches and Rotary Club meetings, always pushing people to think about how to reimagine schools.

The conversations about education don’t stop at home: Riley is married to Swanson, the district innovation director.

While schools were out for two weeks following the hurricane, Riley organized gatherings for teachers at the Tarboro Coffee House, his unofficial office on Main Street. They crafted lesson plans to help students to process the disaster, but also encourage them to think about taking action. Lampron encouraged her teachers to show up, and many did.

Riley’s goal was to avoid a situation where students—even those not hurt by the flood—would see the devastation rained on their friends and then not act, reinforcing the notion that they’re powerless. He thought teachers could help kids take steps to solve immediate needs. “Maybe those steps are tiny, but because kids are taking them, it’s transforming their sense of who they are in relationship to the needs around them,” he says. “That transformation is what I think will yield the most long-term benefits.”

Julia Simmons (E.N.C. ’16) who attended the meetings with Riley, is Ni’zavion’s English teacher at Pattillo. On the first day back in school, she put the new lesson plans to work. Ni’zavion shared with the class that he and his grandparents had been lucky. The water made it up to the bottom of their windows, leaving a mess, but sparing the house. Outside, though, there was trash heaped in piles, scattered across lawns, even draped in the branches of once-submerged trees.

Ni’zavion suggested a clean-up, and Simmons helped him plan it. The next day, he led a charge of 20 students picking up trash all over the neighborhood: dirty diapers, tattered clothing, shredded plastic bags. “Before we even left school grounds, we saw a dead snake,” he says. Simmons met with neighbors who were grateful for the help and inspired that it was coming from kids. For Ni’zavion, it was a taste of leadership at a critical time for the community. “It felt like I was a hero,” he says.

Other Pattillo students stepped up, too. Before schools reopened, sixth grader Zy’Niyah Batts started a kids’ club at the shelter where she was staying. She taught math and English lessons and led the students in a daily motivational gathering based on Pattillo’s weekly “Harambee,” an all-school meeting with inspirational chants and activities.

Several other students took charge of organizing truckloads of incoming donations for displaced families. They turned an unused classroom into a market filled with canned goods, clothing arranged by size, toiletries, and other basics. Even now, students manage it and families can take from the room as needed.

Lampron is particularly proud of student-led initiatives because she and her staff have been trying to nurture those for more than a year. At the beginning of this school year, they incorporated Power Lunch—two 40-minute mid-day blocks, five days per week, for eating and self-selected enrichment classes or extra time with teachers. Students were tasked with coming up with all of the enrichment class ideas. Step Club practices routines in the gym; Gecko Club studies geckos in terrariums built by the school’s resource officer; Unity Club volunteers with students with special needs in Pattillo’s two inclusion classrooms. Any idea is fair game, but it has to come from a student.

Lampron is the last person to say they’ve done enough to prepare Pattillo students to lead outside of the walls of their school. But starting small, she says, is still a start. “Within their own shared space here, they have a voice,” she says. “We’re trying to provide opportunities for them to be able to say, ‘When I didn’t like this about my school environment, this is what I did and this is what changed.’”

Across town, Elijah Sellers is in seventh grade at Martin Millennium Academy, the district’s K-8 magnet school with a focus on student leadership. (Erin Swanson was its founding principal.) He has the gait of someone in charge, hands on hips, chin up. He’s an A student and a member of the school’s Junior Beta Club, a leadership organization for which he was elected the 2016-17 state chaplain. He’s involved with the local Boys and Girls Club and will sign up for any opportunity, like a student camping trip along the banks of the Tar River. Prior to the flood, Elijah had been living in Princeville with his mom and younger brother. After the hurricane, they were among the first to evacuate.

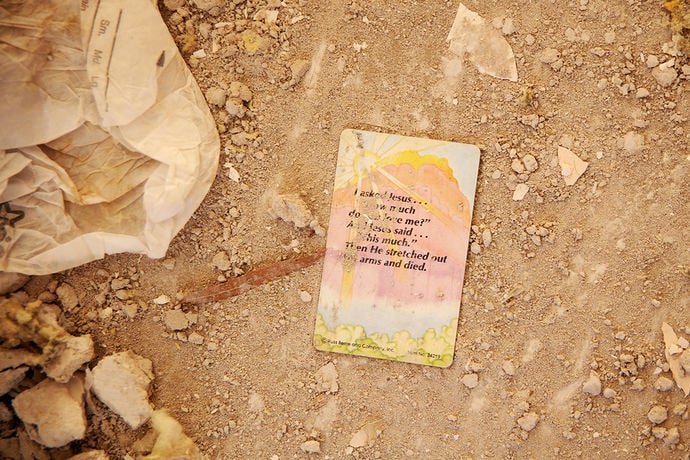

On a frosty day in early December, Elijah led Daniel Riley on a tour of Princeville. For the first time since the floods, he went to his home—a humble rambler in a small development constructed after Hurricane Floyd. He smiled as he stepped through the open doorframe but could barely hide his emotion. Inside, the entire structure was stripped to its studs. Two Legos lay amid rubble on the floor. Elijah crouched to look at a scrap of blue paper. “This right here was hanging on the wall,” he said. “We had little scriptures everywhere on the walls.”

He recalled sitting on the floor with his brother, their mom on the couch, watching TV and playing games on the weekends. He looked out the empty window to the other empty homes and remembered playing on the lawn with neighbors. “We can’t lose that happiness,” he said.

Elijah told Riley that getting through this crisis might be easier if he and his peers could have the space and support to be more open with each other at school. “If we knew more about each other, that would give us a little more respect for each other,” he said. For Riley, the comment sparked an idea: Why not put together a panel of students to come up with ideas for improving their schools and share their ideas with principals and the school board? He promised Elijah would be at the table.

Riley was still thinking about the experience later that day when he arrived at Tarboro’s new brewery for a meeting he’d organized. Ten educators and community members gathered around a long table, sharing resolutions for the new year. Some in attendance vowed to spend more time in students’ homes. One hoped to host a parenting class, mindful in particular of parents whose jobs and homes were thrown into upheaval after the floods. Another proposed a “performance art showcase” at the coffee shop so students could show off their talents and build connections with the community’s business owners.

Riley asked the group to think about the long-term vision for small-town schools to serve kids like Elijah. “And what can we do in this space, right now, to wrench this ocean liner of an education system from wherever we happen to sit to be more in line with that long-term vision?”

The meeting closed with Riley promising to find sponsors to buy the first round of drinks at the next get-together. Those gathered promised to return. “If you care about innovating in education,” Riley said, “we’re gonna do this.”

Resources

- To learn more about Princeville, the oldest town in the U.S. founded by African Americans, and its response to Hurricane Matthew, read “A Wrenching Decision Where Black History and Floods Intertwine,” published on Dec. 9, 2016, in The New York Times.

- Interested in becoming a principal in North Carolina? The Northeast Leadership Academy (NELA) was named one of the top principal preparation programs in the country. Learn more.

- Are you trying to teach your students about a natural disaster and how to take action? The Manitoba Council for International Cooperation has ideas, activities, and lesson plans.

Sign up to receive articles like this in your inbox!

Thanks for signing up!

Content is loading...