Paths Forward for Public Education

As we navigate the greatest upheaval in the modern history of public schooling, what will change, and what must change?

Since March, schools across America have been shut tight against the spread of a pandemic. By the time the new school year rolls around, some students will have been out of their school buildings for six months. Our modern nation has never been through an upheaval like this. Neither has public education.

Beginning in March through mid-May, we asked teachers, parents, and dozens of Teach For America alumni: What’s next? After the quarantine phase of this catastrophe recedes and we return to school, how might public education be permanently changed?

The point on which we heard unanimous agreement was that students’ unequal access to technology and the internet is a national crisis, now that digital learning is here to stay as a function and feature of school life. “There will never be another snow day” now that we know we can just log in to school, said Brandy R. Nelson (N.Y. ’97), the executive director of teaching and learning for Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools in North Carolina.

We heard widespread confidence that public demand will force policymakers to close the digital divide for the same reason that following the Great Depression, the federal government started funding rural cooperatives to electrify (almost) all of America: because internet is a now a utility that people need to live.

Beyond those points of agreement, we found few willing to say what definitively will change. But most had opinions on what must.

John King, the former U.S. secretary of education and current CEO of The Education Trust, said, “Ideally, we would have a ‘New Deal’ moment where we come out of this crisis more deeply committed to each other, more deeply committed to strengthening our social safety net, and ready to rectify longstanding educational inequities.”

There’s a perfect storm coming as school systems brace for potentially huge state and local budget cuts, even as the mental health and learning needs of students balloon. King called on federal lawmakers to provide “an immediate infusion of funds to save school districts from terrible cuts” and for states to organize “how to spend these funds to further equity.”

“We know that schools that serve high numbers of low-income students and students of color have less access to resources, well-prepared teachers, advanced coursework, counselors,” and support to prepare students for higher education, he said. As unemployment spikes and poverty engulfs more families, “it is—again—these same students who face the greatest inequities,” King said.

We also heard from skeptics like Shannon Wheatley (R.G.V. ’04), the chief academic officer at two schools in Oakland, California. It’s worth remembering that many of the benefits of the Great Depression’s New Deal excluded people of color and reinforced discrimination. Speaking of the current day, Wheatley said, “The institutions aren’t going to change. They don’t have the incentive to do anything different. There’s too much power invested in the way things were.”

Public education has an “incredible track record of resuming its original shape after a crisis,” said Dale Chu (R.G.V. ’97), a senior visiting fellow at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The CEO of TNTP, Dan Weisberg, said, “The biggest risk is nothing will be fundamentally different. Without those of us who have a platform working really hard, we will go back to the default. The same relationships. The same inequity.”

Aylon Samouha, co-founder of the school innovation nonprofit Transcend, warned, “If we don’t seize the moment now, could you imagine trying to convince a funder or a policymaker that they should put time and money into ‘reinvention’ later? If we don’t support at least a few thousand schools to be in a very different place in a few years than they are today, we will have squandered this inflection point.”

Then there are leaders like the founder of thinkLaw, Colin Seale, who works with schools in 30 states to emphasize critical thinking. Seale says to resist using the language of reinvention. Instead take this moment to ask the most practical questions about how students most damaged by inequity will learn differently. Then build a plan to answer, “What does this look like on a Tuesday morning in February?”

Seale said, “Let’s focus on what’s the best way to help students use the power they bring to the table to impact their learning, and then let’s take stock, do an inventory of who in the community can check the equity question. Enough garbage about what our communities can’t do. You know how long we’ve had to work through these challenges on our own? You don’t think there’s enough institutional knowledge out there to work through this one?”

This article rests on a provocation. Come next school year, school budgets will almost certainly be cut. And “kids will walk in with trauma, with their personal lives upside down, with much larger than normal learning loss,” Weisberg said. “If we just say to teachers, ‘Go: You have 180 days to catch up from last year and then also do this year’s work,’ that will be low expectations on steroids.”

So where do you see a lever to pull, and how will you pull it? Here’s what we heard from around the country.

Parents and Teachers Will Tap Their Advocacy Power

Jametta Lilly CEO, Detroit Parent Network

Jametta Lilly observed that COVID-19, which infiltrated Detroit and led to one of the nation’s highest death rates, “rips the veil off for anyone who has been deluding themselves that somehow or other we have an equitable system in health or education. This happened so quickly, people didn’t have time to align their talking points to gloss over it.”

Lilly is looking for new openings to emerge for partnerships between Detroit schools and community-based organizations to support families in the short term (helping parents manage home instruction and providing summer enrichments). And in the longer term, she’s looking toward partnerships to bring more wrap-around services to schools.

“COVID presents some opportunities that perhaps parents haven’t had before,” Lilly said, to advocate for policies to improve teacher development in ways that are “highly culturally competent,” and also policies to boost the holistic well-being of families. Building out school and community partnerships “is not rocket science, but it’s not being done because people don’t value it enough to fund it.”

Detroit Parent Network has been broadcasting webinars to update parents on the Detroit school district’s work to expand internet access and adjust grading and graduation policies. At the same time, the organization has been connecting parents to policy and advocacy actions. “Parents and family advocates more than ever need to turn up the heat on education, health and mental health and human service organizations as a whole to say, ‘How can we partner with you?’ And in ways that are equitable and empowering.”

“For parents who are politically and socially aware,” Lilly said, “it’s not a small notion that we’re in an election year. I am hopeful that one thing that gets back on the table is genuinely improving our health care system, because it absolutely affects education.”

Johari Matthews Executive Director, Northwest YMCA in Nashville, Tennessee and Co-Chair, Women of Color for Education Equity

“I don’t think we’ll have the option of returning to normal because I don’t think parents will let us,” Matthews said. “I think you will have a rise in parents who understand that traditional schooling isn’t their only option.”

Parents who are neck-deep in virtual learning are “becoming really aware of the curriculum and more in tune with what their children are doing academically.” Some are shocked and alarmed at the disparities and vast differences they’re seeing in what various schools and systems and teachers are offering students. Parents are “finding their networks,” Matthews said, and some are “feeling empowered to make [schooling] work on their own.”

Matthews’ son attends kindergarten at Nashville’s Purpose Preparatory Academy, which made the choice to go full force on academics during the shutdown. Other parents have asked her to pass along her son’s assignments.

She said, “You have parents who have been advocating and fighting for better schools for a long time, but when you’re in a situation that affects everybody no matter your income level, race, or status, unfortunately that’s when you have more people wanting to get involved. Oftentimes when issues directly affect a marginalized group, they tend to go overlooked and we don’t give people the basic resources that they need to thrive.”

Matthews predicted “you’ll have a lot of parents of various backgrounds fighting for the same things,” including adequate school funding as tax revenues fall.

Jonathan Santos Silva (South Dakota ’10) Founder, Liber Institute in Rapid City, South Dakota

As a TNTP Bridge Fellow, Santos Silva spent a large part of last year meeting with students, families, educators, and elders in tribal communities including Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Standing Rock, and Sisseton Wahpeton. His aim is to build a leadership institute that will prepare educators to launch schools that redress the inequities Indigenous students experience.

Santos Silva is singularly focused on parent demand. “If I have any hope that this pandemic will improve public education and address its inherent inequities, it hinges upon parents demanding that we won’t go back to the old ways,” he said. “Government and business will never push for the sort of whole-scale change we need in public education, especially when we think about Indigenous students and families and the many ways in which the public education system has treated them inequitably. You have to make it uncomfortable for people in power.”

Jaisha Haynes (New Mexico ’18) Fifth Grade Teacher at Rocky View Elementary School in Gallup, New Mexico

Haynes (who was taught by corps members as a child in Atlanta) went to work the day before the district’s scheduled spring break and never got to say good-bye for the year to her fifth graders. Because not all families have the means to communicate in the crisis, she says she understood that her district instructed teachers not to be in touch with students and families so as not to provide unequal access to some. In April she said, “I choose to serve in a community, and now I am completely cut off. I feel alone.”

She predicts, though, that both teachers and families will emerge from this crisis advocating for greater involvement in local decision-making. “If parents had input into how money is spent,” she said, “perhaps our students would have the resources such as laptops and the internet that are contributing to this inequity right now...Perhaps we would already be prepared and equipped so education can continue.”

Erica Jordan-Thomas (Charlotte-Piedmont Triad ’08) CEO of EJT Consulting in Charlotte, North Carolina, Doctoral Student at Harvard Graduate School of Education, and Chair of the National Advisory Board of The Collective, Teach For America’s association of alumni who identify as Native, Indigenous, and people of color

A former principal in Charlotte, Jordan-Thomas sees parents getting a crash course in who holds the power within education ecosystems. “Folks have some understanding of what a teacher does, and people can conceptualize the role of the principal,” Jordan-Thomas said. “It’s harder for the average person to conceptualize the role of a school board or a state department of education. COVID-19 is putting a spotlight on the roles of school boards and state departments.”

But now that voters have seen school boards can change grading and promotion policies overnight and call off standardized testing, she believes more will turn out to vote in school board elections. Because they’ve seen the state can shut down districts for months on end, she hopes more will understand the power of state departments and advocate there.

Jordan-Thomas can’t help adding that she hopes the crisis will increase empathy among state education leaders and elected school boards. They just had to re-invent school systems on the fly while responding to confusing and conflicting mandates. “That’s what every day is like for a Title I school principal,” Jordan-Thomas said.

Fareeha Waheed (Baltimore ’14) Special Education Teacher at Eutaw Marshburn Elementary School in Baltimore, Vice President of Elementary in her teachers union’s local

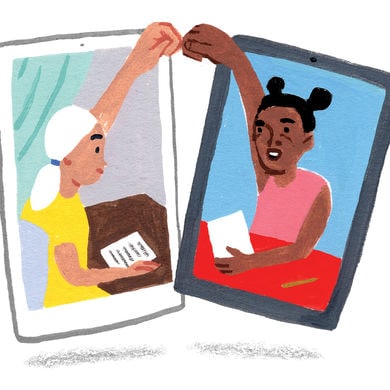

Waheed says her constant back-and-forth with parents who are leading learning from home gives her hope. “Education has been a spectator sport. Now it’s become a team effort.”

In what she called “the largest education crisis we’ll ever see in our lifetime,” Waheed saw her school district distribute educational packets to students and creatively leverage outlets to reach students, including broadcasting lessons on local TV stations. She also saw some students not getting what they needed, “such as access to a nurse or [help with] psychological needs, even a place to get a warm meal.”

She believes a long-simmering inequity in her students’ access to laptops and connectivity will finally be addressed as comparisons to neighboring districts are revealed. At her school, students rarely use laptops, she said, yet they’re assessed frequently in that format. “How can we begin to talk about a free and public education when technology is the barrier to do that?”

Austin Reid (Kansas City ’12) Education Committee Director, National Conference of State Legislatures in Washington, D.C.

“The pandemic has put pervasive inequities into the spotlight, and many people have speculated that will be the impetus for change,” Reid said. But apart from tacticians, he’s hearing few discuss “the challenges to making that change.”

Take arcane state educational funding formulas, in many places the machinery of inequity. In an election year when state legislators face catastrophic budget shortfalls, “revising a funding formula is a very tough lift.”

Or consider services provided by schools that fall outside of states’ mandates. Schools may need more counselors, Reid said, but discretionary dollars are often the first to disappear in financial crises. Advocates will need to get creative. “Others will have ideas, too. You don’t need to agree with them, but it’s important to understand their thinking when advocating for a share of scarce resources.”

Advocates may see new possibilities after November. “But if we can figure out ways to serve students better now, even with fewer resources,” Reid said, “those strategies will be even more valuable down the road when things are hopefully back to normal.”

Things Don’t Have to Be So Complicated

Eric Leslie (Greater Philadelphia ’04) Founder and Lead Organizer, Union Capital Boston (UCB)

UCB is a network of about 2,000 Boston residents, many of whom live paycheck-to-paycheck in mostly lower-income neighborhoods. They organize, advocate, and volunteer on civic efforts and earn monetary awards through a mobile-app loyalty program.

UCB moved into crisis mode on March 9, the day the first big local institution (Harvard University) shut down and members started losing their jobs. Leslie said, “I realized that what matters most in a crisis, when people are not going to have a paycheck next week, is for people to have immediate, efficient, access to resources which cannot come with all these stipulations. There can’t be bureaucratic red tape.

“My no-brainer idea was to realize that we have an efficient infrastructure to be able to help. We’ve been ordering Visa gift cards for the past five years for people in need. We could set up a system to get cash in peoples’ pockets in a week, and we could do it safely.” With its staff of three, UCB rolled out $150,000 in cash gift cards to 1,000 families in a week and had distributed more than $300,000 to more than 2,000 gift card recipients by early May.

Leslie’s insight was that “our largest, most inefficient and complex systems—education and health care—were the ones buckling under this crisis.”

“I’ve been meditating a lot on structural efficiency and I don’t know what the answer is for education systems,” Leslie said. But he sees two things potentially happening: smaller, frictionless outfits like his scaling up without adding inefficiencies, and vast, change-resistant systems beginning to shed accumulated rules and infrastructure to evolve more nimbly.

We Can’t Un-See Students’ Unmet Basic Needs

Everton “EJ” Blair Jr. (Metro Atlanta ’13) Member, Gwinnett County (Georgia) School Board

Blair, who started his career as a geometry teacher at KIPP Atlanta Collegiate High School, is the first person of color, first openly gay, youngest ever elected board member in Georgia’s largest school district. One month into a profoundly disrupted school semester, he said, “People are being a lot more receptive in giving kids grace for conditions and circumstances that they had no part in creating. I’ve seen people who are normally the most resistant being so on board with this, and it’s refreshing.”

“A virus that we can’t even see has challenged all of our notions of what needs to happen for kids, and why. We’re recognizing that if kids are hungry, we need to feed them. If they don’t have access to a laptop, we need to find one. We’re finally illuminating the ways the system can change quickly to address chronic needs,” Blair said.

“All these provisions that we’ve so seamlessly been able to find money for during a pandemic—let’s not forget that kids will still need those exact same things when we go back, and even more so” as the economic fall-out of COVID-19 throws parents and guardians out of jobs and destabilizes family life for millions.

Students should be brought into plans to evolve schools because they will bring strengths, fresh experience, and good ideas, Blair said. “To some extent they’re teaching themselves right now and peer-facilitating learning with other students.”

Josephine MacLean (New Mexico ’19) 12th grade government teacher at Gallup High School in Gallup, New Mexico

During the first two weeks of district shutdown, MacLean was scrambling to help families meet their immediate needs. She fielded questions about what would happen with graduation and about food and internet access while other school staff members boarded buses to deliver meals to students. Many live within the bordering Navajo Nation, which in May surpassed New York State for the highest per-capita rate of confirmed coronavirus cases in the country.

A lack of widespread internet access made online learning virtually impossible, MacLean said. “Many of our students are used to worrying about having water and heat at home, let alone the internet.” When school resumes, MacLean and her department chair at Gallup High plan to require more online engagement from students, not less.

It may seem counterintuitive when students don’t have home access, but MacLean says the crisis has exposed that online literacy is more critical than ever not only for schoolwork, but to find reliable news and information. “We’re planning to require them to watch videos and do other online work outside of class. That might mean they need to go to the library during a free period or after school, and that’s fine. This is a skill students need whether they have access at home or not.”

Still, she worries that will be insufficient as districts manage waves of shutdowns and students return to unconnected homes. “I’d always debated if the U.S. should adopt internet access as a basic right. This has made it really clear to me that we should.”

Oscar Hernandez Ortiz (Phoenix ’18) Fifth Grade Teacher, Collier Elementary School in Avondale, Arizona, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipient

Hernandez Ortiz is especially concerned that undocumented families, worried about disclosing their status, are missing medical treatment as COVID-19 spreads. That could have catastrophic effects on students and their parents. “A completely undocumented family knows they don’t have that access,” he said. “They are intimidated or scared to go; you know you are only going to go to the doctor if you are really sick or about to die…There are all of these invisible barriers undocumented families have to navigate, and the kids know that.”

“There’s always a tension when teachers want to help and leadership is worried about the political fallout,” Hernandez Ortiz said. “It’s a sensitive subject that many do not want to talk about, so we continue to have kids not see doctors.”

We Could Go Back to the Future

Zak Ringelstein (Phoenix ’08) Founder and CEO of learning app Zigazoo, doctoral student at Teachers College of Columbia University, former Democratic candidate for U.S. Senate from Maine

“Now that everyone is home, kids are making it pretty clear to their parents, through their emotions or their body language, when they don’t want to do some kind of learning that is rote and pretty boring,” Zingelstein said. “Families are almost forced to do more project-based learning right now. Kids won’t engage in a random fraction worksheet, but they’ll break up a pizza into fractions if you make a pizza with them.”

“What’s breaking wide open is our appreciation for a type of learning that is more humanistic and natural. It’s the fundamental idea that kids aren’t supposed to sit at a desk all day. One of the interesting things that organizations like the American Federation of Teachers is promoting is to give kids capstone projects to do, because work that kids care about is more likely to actually get done right now.

“What we’re doing with our app is giving kids prompts. Can you build an obstacle course? One of our most popular ones is: can you free a toy from ice? Kids answer the prompts and share a short-form video. We’re on mobile because it’s more accessible than most edtech, which requires a laptop.

“I think we’re at an ah-ha moment for educators and parents where we can build tools for how kids want to learn as opposed to how they’re forced to learn.”

Eugenio Longoria Sáenz (D.C. Region ’97) Education Faculty at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley in Brownsville, Texas

New problems require new solutions, sometimes. But to meet the moment, Longoria Sáenz said, what if we re-emphasized doing things we’ve long known should be done? Teachers know that building community with students and family is fundamental, but often feel other priorities take precedence. Once schools closed, Longoria Sáenz said, teachers found space to renew their focus on relationships. Stories emerged in viral videos of teachers caravanning through neighborhoods and “adopting” former students who became stranded seniors, sending them care packages and advice before they graduate.

When the students in his college class were forced online, the experience brought them together. In a final class session, students expressed how much they’d miss it. “I told them, ‘The reason you’ll miss this is because we were a community,’ ” Longoria Sáenz said. “We weren’t just a class you came to every week. As a future teacher, you need to do that in every one of your classrooms.”

“We talk about duties, responsibilities, delivering instruction. More important than any of that, build a community, and all that other stuff will fall in place.”

Students Should Take the Lead

Maureen Ferry (Bay Area ’05) Principal, Exceed Charter School), Brooklyn, New York

Ferry’s network decided on a Friday to close schools and by that Sunday, all New York City schools were shut down. Teachers contacted all families and by that Tuesday, had a plan to get a Chromebook to any family who needed one. Though the school had never used Google Classrooms, teachers took Wednesday through Friday to train up. They kicked off asynchronous distance learning on Monday. Within days, Ferry said, “I had teachers share that we can’t go back to the way we were. No way.”

Ferry predicted her school will move toward giving students more agency over their learning. “As much as we tried pre-COVID, we have a long way to go. So much of our students’ daily learning experiences are driven by rigid schedules and plans.”

Now with asynchronous distance learning, students can access lessons at any hour. “They have to manage their time and make decisions for themselves about what to do and when.” Some students are struggling “but more are loving it,” Ferry said, and some students are producing stronger work than when classes were timed and structured. In addition, teachers are being challenged in new ways and “some of our teachers who are artists are finding the creative challenges to their practice energizing.”

Ferry predicts schools will shift to giving students more ways to pace and structure how they learn, which will better prepare them for independence and self-advocacy in high school and college. She can imagine teachers switching some class hours to office hours where they oversee independent learning.

“There’s so much we need to be doing and hadn’t been doing prior to this shutdown” to hybridize learning and grow student agency, she said. “We talk about how the school system is archaic and has changed so minimally in the last century. In a lot of ways this is the shake-up that everyone knew was necessary.”

Shannon Wheatley (R.G.V. ’04) Chief Academic Officer, Lighthouse Community Public Schools in Oakland, California

Wheatley sees potential for long-term impact at the student level as this crisis puts more students in charge of their learning. ““We are seeing students take more responsibility for their own learning than ever before. Young people can learn much more than we often let them. I don’t think this will change, and I believe that’s for the better.”

JoAnn Gama (R.G.V. ’97) CEO and Superintendent, IDEA Public Schools in Weslaco, Texas

Gama is pleased to see how 51,000 students have traded places with their teachers as IDEA schools have moved to virtual learning. “Historically, we have struggled with the reality that our teachers do too much of the ‘heavy lifting’ for kids,” she said. “We continually coach our teachers to do more facilitating and less direct teaching. Kids should be exhausted at the end of the class period, not teachers. But again and again we would see teachers doing the majority of the heavy lifting. Through distance learning, I am seeing the students do the majority of the work. Now we are saying: ‘How do we incorporate this when we come back in the fall?’”

Cultural Competency Grows More Urgent

Angela Kwak (Greater Philadelphia ’18) Fifth Grade Teacher, Mastery Charter Thomas Elementary School in Philadelphia

One thing that moving to distance learning has changed, Kwak said, is that “we’ve all learned to be more empathetic with one another,” as educators and families can literally see through their screens into each other’s lives. “Everyone—students, teachers—has conditions at home that we didn’t know about, and we have to be aware and extend that empathy more than we have before.

“So while the focus of schools is still on academics,” Kwak said, “we’ll have to make more moments and community spaces for students to express what they’re feeling and going through.”

With her students, Kwak is preparing to more directly address racial stereotyping that results from students’ incomplete grounding in American history. At age 10 they don’t understand the stereotyped language they hear or why fractious relationships grew up among ethnic and racial groups in places like South Philadelphia, where she teaches.

The way the virus has unleashed anti-Asian and Asian American racism and violence “has brought out a need for allyship,” Kwak said. “When we go back to school, there has to be a bigger focus on identity-building and an understanding of the relationships between communities of color,” starting with improved professional development for teachers to develop cultural competency.

Sam Lim (Metro Atlanta ’18) Science and Social Studies Teacher, The S.T.E.A.M. Academy at Carver High School in Atlanta, and Founding Member of the Atlanta Prism LGBTQ+ Coalition

Four weeks into the shutdown of schools in Atlanta, Lim had been able to connect online with only 20 of his more than 150 students. The rest included students who lacked devices, who were living in substandard housing without wiring, or whose families had debt or credit histories that boxed them out of temporary “free” internet.

In mid-April, Lim was in contact by phone with students whose water had been shut off. Others had scattered outside the city. Lim and members of the Atlanta Prism Coalition were working with a network of partners, including Atlanta Pride, to find students and connect them with basic resources including food. He sees these organizational partnerships growing tighter as members are in daily contact to track down students, and stronger advocacy will emerge from “really being pushed to be intersectional.”

“What’s honestly most frustrating to me is trying to work with people in high-profile jobs who have no understanding of our students’ families or communities,” Lim said. “I was meeting with the chief of staff at another charter organization to see if he could get a student I mentor a hot spot. I’m telling him that this family is having a hard time buying groceries, they don’t live in a stable apartment, and his solution is to ask if the family can buy a Verizon package.”

“This is even more true when we talk about the crisis with LGBTQ+ youth in Atlanta.” Pointing to the rise during the pandemic of minors calling the National Sexual Assault Hotline, Lim said, “We estimate that about one third of homeless youth in Atlanta are LGBTQ+ youth. The shelters are closing, which puts them at even greater risk. I know schools are thinking about planning ahead for the fall, but if we can’t keep them safe now—the students who are the most marginalized in our communities—we’re not going to have those students next year.”

Pi‘ikea Kalakau-Baarde (Hawai'i’15) Resource Teacher supporting schools on Hawai‘i’s leeward coast to provide educational opportunities tied to Native Hawaiian culture and practices

In a matter of weeks, the pandemic drove Hawai‘i’s unemployment rate from 3% to more than a third of the state. Schools are especially vulnerable to a crumbling economy as Hawai‘i is the only state not to use local property tax revenue to fund education. By mid-April, state leaders were considering pay cuts for all state workers, with some floating the idea of a 20% cut for teachers.

Kalakau-Baarde, who was a state legislative aide before becoming a teacher, is buoyed by the “feminist economic recovery plan” proposed by Hawai‘i’s Commission on the Status of Women. It recognizes that female-dominated professions, like nursing and teaching, are the backbone of community survival and must be well-compensated.

Native Hawaiian values are finding expression amid the crisis, too, Kalakau-Baarde said, like the farmers on Oahu’s rural west coast distributing food to students. “The Native Hawaiian groups are the ones saying we need to use this as an opportunity to reform our economy. Take care of family, take care of land, and the land takes care of you.”

Hybrid Systems Will Force Change

Alonna Berry (Jacksonville ’11) Founder, The Bryan Allen Stevenson School of Excellence, scheduled to open in 2022 in Sussex County, Delaware

“Delaware has had a really tough time,” Berry said. “Our kids were out of school with no instruction or access to anything for two weeks. Here in a rural community, some schools have popped up some learning and distributed packets, but it’s still not deep learning.

“As a person who is planning a high school right now, it’s an eye opener to rethink what we’ll need. We’ve been having a series of webinars with parents and students and community members to engage with their input.

“One thing we realize is that this won’t be the last time schools close,” Berry said. “Schools need to be able to flip a switch on any day and say, ‘We’re virtual now.’ We hadn’t planned on being one-to-one right away, but now we have a unique opportunity to make sure that every kid has a device and every family has access to the internet. That could mean engaging philanthropy and local partners like Comcast, which provides cable, to see if we can talk about things like donations of hot spots.

“We’re planning for a mental health clinic in our school, but we need a policy implemented nationally to have mental health services for all kids regardless of who has insurance or the ability to pay for it,” Berry said. “I would hope to see that policy change, but it won’t happen fast enough for kids. Our goal is to be a service-learning high school, and now is a chance to model for students how to get that going.”

Sam Kary (Bay Area ‘10) Founder, YouTube Channel The New EdTech Classroom, Sixth Grade Humanities Teacher, Gateway Public Schools in San Francisco

“There are three things that I think will change, or should change,” Kary said. Families will get universal access to the internet, schools will adopt higher standards for technological literacy, and differentiated teaching tools and advanced learning devices will proliferate.

“With companies working now to bring Wi-Fi to people who don’t have it, they will not be willing to go back to living without the internet. And for families that got computers from their schools,” Kary said, “how do you ask them to give them back?”

On tools: “I hope this opens up a conversation about the need for all students to have one-to-one devices. I would go further and say students need access to a tablet, which is more of a creativity device, and schools should provide equitable access to more advanced hardware like virtual reality headsets and 3D printing machines.”

On tech learning standards: “My hope is that this forced pivot will start a national conversation about adopting technology learning standards for students in the same way there’s been a conversation about adopting common core standards … An exposing feature of this moment is we see that the people who are able to thrive are people who have access to those more advanced technology skills.

“And just like GPS is a better tool for navigation than looking at a paper map, there are ways in which tech tools are inarguably superior for some kinds of learning. When it comes to personalizing instruction for English language learners or a full-inclusion general education class—or teaching a class in which students are reading anywhere from a first to ninth grade level—the tools are right there to give students readings on their Lexile level so they can do grade-level work. Everybody who teaches is being forced to use those tools, which makes this a moment where we’re really poised to launch into that more holistic integration of technology in learning.”

Heather Harding (E.N.C. ’92) Director of Education Grantmaking, Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation

Harding is responsible for grantmaking that seeks to leverage educational opportunities that drive the economic mobility of students of color from low-income backgrounds. As she reflects on how the entire country has been “thrust into digital learning in a totally different way,” she is most focused on “how we can learn from this grand, unplanned experiment to provide teachers with the tools, platforms, and devices—but more importantly, instructional and pedagogical approaches—that reflect what we know works.”

As a parent who has been listening to other parents and watching the comments pile up on a list-serve, she is clear that parents will demand a hybrid approach to education that marries in-person, on-line, group, and independent learning. “Too many students and families are seeing the power of personalized and online learning” to give it up.

Stephanie Downey Toledo (L.A. ’03) Superintendent of Schools, Central Falls School District in Rhode Island

As schools closed and distance learning launched, Downey Toledo’s first challenge was access. Central Falls had 1,000 devices for 3,000 students and significant broadband needs. She and her team worked quickly to ensure every household had a device. For some families this meant four students jockeying for access to one device, necessitating her schools to create a master schedule that lessened overlap. Local internet providers have donated two free months to all families who need it, leaving Downey Toledo hopeful for a long-term low- or no-cost solution.

To solve that problem and more, Downey Toledo is most excited about the unprecedented cross-sector collaboration she’s experiencing in Central Falls and Rhode Island. “I am seeing collaboration across all of the dimensions: schools, departments, families, and teachers. I am watching everyone support one another and collaborate in a way that has never happened before. People are saying ‘We could have been doing this before.’”

She said, “In a district where a majority of the students speak multiple languages and a majority of the teachers are mono-lingual English speakers,” educators have been turning to tools like Google Translate to work more closely with families than before the pandemic. She’s hoping to see gains grow from educators incorporating new tools and parents responding enthusiastically beyond the pandemic.

Michele Caracappa (N.Y. ’02) Chief Program Officer, New Leaders in New York City

Caracappa’s programmatic work has her thinking about the lessons districts and networks will learn from schools and systems that have a highly cohesive school culture and clear expectations.

Caracappa cited how quickly Success Academies was able to restart and troubleshoot online learning. “It is a mistake to think that the success at Success is about technology rather than culture,” she said. “The groundwork for a smooth transition had been laid already with clear expectations for teachers, students, and families and an already frequent level of communication and investment between families and schools.”

She pointed to Baltimore City Public Schools and the culture that CEO Sonja Brookins Santelises and the district’s team have built. “Everyone [in the system] is already rowing in the same direction. They are going to lose so much less time and momentum” in advance of school reopening, Caracappa said. “Forget anything about technology or remote learning or access to devices prior to the crisis. The school systems with the strongest and most unified cultures are the ones who had a head start.”

The Invisible Will Become Visible

Niloy Gangopadhyay (Bay Area ’02) Director of Special Populations,Texas Education Agency in Austin

Gangopadhyay, who previously founded schools in Cleveland and New Orleans, has spent the last year supporting education for English learners, students who are experiencing homelessness or in foster care, students who are pregnant or have been trafficked, and gifted and talented students in Texas.

One change he expects to see is a recognition of just how significant the number of English language learners are, and how focusing on their instruction could significantly drive higher achievement in rural as well as big city school systems. He noticed in his first year at the Texas Education Agency that few districts have what Gangopadhyay calls “C-suite” leaders of instruction for English language learners.

In the shift to distance learning, districts faced a significant challenge in supporting their English learners who comprise 20% of all kids in Texas and up to a third in border districts.

He imagines educators will develop new online content for linguistically diverse learners that are just as available online to sparsely-staffed rural districts as to big cities. “We can shake things up,” he said.

Aleesia Johnson (New Jersey ’02) Superintendent, Indianapolis Public Schools

“When we think about returning back to ‘normal’ there are parts of that normal we don’t want to return to and we don’t want to perpetuate,” Johnson said in early May. “I’m asking my cabinet: ‘What would be true in a radically equitable world? We will start with the assumption of excellent outcomes for all students and then we’ll dive into what inputs and conditions must be true to achieve this outcome. We’ll wrap up this work by determining which of those we have total or partial control over.”

Johnson knows districts can’t assume students will all pour back into classrooms and sit side-by-side in the coming school year or play together on a sports team. Social distancing might require class sizes to shrink or students to stagger their schedules. Johnson is trying to see beyond how school buildings were used to how they could be.

“In doing our chief job of keeping students safe in the near and perhaps medium term, we’re forced to make changes that will have profound impacts on the ways in which we cultivate relationships between students and adults and among students,” she said. “We’ve worked hard to build spaces and environments that foster collaboration, group work and interaction. These scenarios are the very same ones that pose health risks for everyone in a school.” She added, “We know authentic, strong relationships between teachers and classmates often evolve through extracurriculars in settings where students and adults can show off their strengths in different ways.”

That conceptual thinking is hard, she conceded. “As human beings, we like the comfort of what we know. What is known was working for a particular group of students in this country and not working for many other groups of students. We’ve got to balance the tension of wanting to create stability (in a time that’s destabilizing) with naming and identifying places where we don’t want to continue to perpetuate things that are also destabilizing and inequitable.”

Building Better Systems

For a map of what lies ahead, we spoke to Emily Freitag (S. Louisiana ’04), the CEO of the school support organization Instruction Partners and Tennessee’s former assistant commissioner of curriculum and instruction. Her organization is developing scenarios for schools, districts, and networks to evolve through the same four chapters that public health organizations use: crisis, re-entry, recovery, and new normal.

Her work keeps her close to superintendents and school leaders who are trying to engineer better systems by watching what’s changing now. “Teachers are thrust into the lives of their students—and vice versa—in a very different way than when school was the meeting ground,” Freitag said. “Today, teachers are seeing their students’ homes and hearing about how they’re spending time in a wholly different manner.

“It’s creating a different type of relationship and way of thinking about what students need. The idea that we don’t have to do the same thing for everyone and that we can give students who need more help more help—we’ll have new models for how to do that.”

Freitag conceptualizes another set of key changes as “things we are getting used to that we won’t want to change.” She sees high schools operating differently from early grades with fast change on the way. “You try to tell a 16-year-old that they have to go to school at 7 a.m. It’s not going to happen. High school will look more like junior college.” If leaders give it a coordinated hard push, this could accelerate a trend away from seat time to students earning credit hours based on mastery. “There is enormous appetite for making this change now,” Freitag said, “but it will take advocacy, policy change, and coalition building.”

One Day magazine focuses on educational equity. What topics most interest you? Tell us.

Sign up to receive articles like this in your inbox!

Thanks for signing up!

Content is loading...