LGBTQ Pride Month: Where We Are and What Educators Can Do Right Now

June 6, 2016

June is LGBTQ Pride Month, and there’s no doubt that we’ve made significant strides toward social justice that deserve to be celebrated. Last year, the LGBTQ community celebrated the passage of federal marriage equality. A few months earlier, I had been named the GLSEN Educator of the Year, a personal milestone that made 2015 even more unforgettable.

A year later, it’s still important to appreciate the federal protection of same-sex marriage and all it implies, yet it’s equally important to continue to push forward and demand equity for students in every classroom and LGBTQ educators throughout the country. I’m deeply engaged in this work for the many Americans seeking LGBTQ equality, including so many of the students I teach and serve at McKinley Tech in Washington, D.C.

Exciting Times to Be a Teacher, But Much to Be Done

Just this year, the U.S. Department of Education released the Dear Colleague Letter, coupled with Examples of Policies and Emerging Practices for Supporting Transgender Students. These documents represent a historic step in the right direction for LGBTQ students, advisors, and their allies. When placed in the right hands, these policy guidelines will serve as a framework for local school activists to begin shifting the paradigm of discrimination, prejudice, and injustice that LGBTQ youth experience all too often.

Alongside the current policy’s implications for transgender youth, I believe that we need to continue our focus on LGBT youth and youth of color, and continue to push for national mandates that will require noncompliant states to create policies that will protect all youth. Only then will we begin to alter the trajectories for our youth on a national scale. After all, queer youth of color are especially at risk of dropping out of high school or falling into the school-to-prison pipeline as a consequence of engrained practices and zero-tolerance approaches. According to research conducted by the GSA Network, queer youth of color make up only 6 percent of the population but account for a whopping 15 percent of the juvenile justice system. For far too long, our country’s broken education system has systemically oppressed the very students who are most at risk.

As a queer, white, cisgender teacher of predominately queer youth of color, understanding these statistics and their implications for the youth I choose to serve is pivotal to my success as a teacher and a GSA sponsor at my school. (GSA is a student-run club that brings together LGBTQI+ and straight students to support one another, provide a safe place to socialize, and create a platform to fight for racial, gender, LGBTQ, and economic justice.) We have to begin to shift the conversation and the focus of our community onto the very youth who are most at risk for suicide, depression, violence, and injustice. We, as a community, must stand up and demand better.

And we also have to hold school systems accountable for supporting their LGBTQ youth and teachers. Far too many educators are still closeted, for fear of retribution by their school community, administration, or school system. The law simply is not consistent from state to state, which creates cultures of fear centered on gender and sexual orientation.

Speaking From Personal Experience

I remember very well the days when I, too, was closeted in the classroom. It wasn’t until after starting the GSA at McKinley, and developing a positive schoolwide culture of radical acceptance and support, that I finally felt supported and safe to come out: first to the GSA, and then to my general-education classroom. Bringing my queer identity and whole self to the classroom has enabled me to be a better educator and break down barriers that exist all too often in classrooms throughout our country.

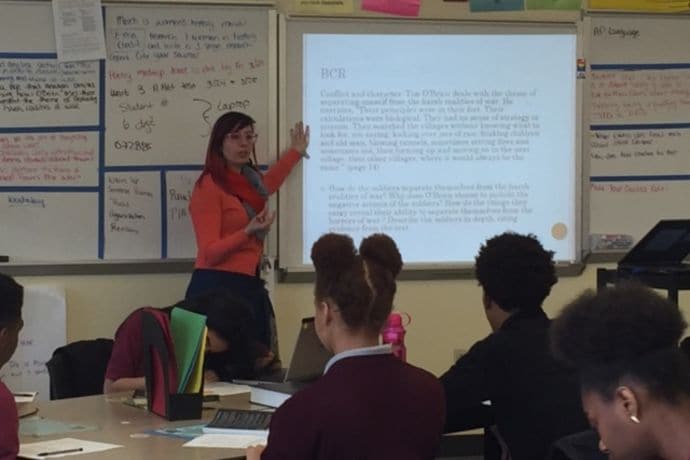

Now, I’m able to use best practices for LGBT youth in my classroom in positive, affirming ways: implementing LGBTQ voices in my curriculum, revising my classroom rules to include language of acceptance, and displaying supportive flyers and posters are all steps that I take to ensure my students feel safe. I also recently synthesized legal documents from the District of Columbia Public Schools and the Dear Colleague Letter and hosted a professional development workshop for teachers at my school. The feedback I received after the workshop was so supportive; all the attendees wanted more time to engage in this type of professional development, and have asked me to host more opportunities like this for our school community.

My students continue to thrive, outperforming district-set bars for growth. I believe that this exponential learning is the result of a culture of empowerment and support: empowered teachers encourage and empower students to learn. This is why we need federal mandates that protect LGBTQ youth and educators, and real consequences for administrators and school officials who ignore the law.