'Teaching is My Form of Activism': Asian Pacific American Heritage Month

How Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders are playing a key role in the fight for educational equity for all.

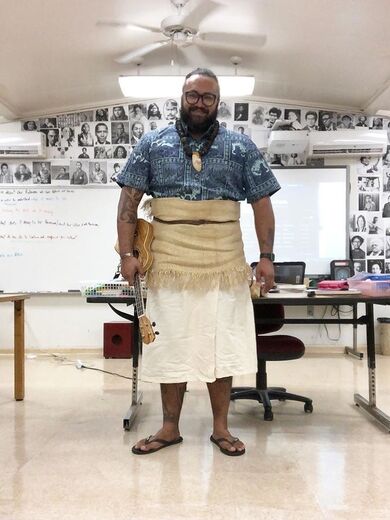

The first time Kiliona Palauni read a book by an author who shared his identity was at the age of 26. Growing up in Utah and Idaho as a member of the Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander diaspora, he never had a teacher who shared his identity or validated his background. In history class, he never even saw Hawai’i on a map.

“Growing up, I never knew anybody that was brown that ever went to higher education,” Kiliona says. “It really affected me. I really only thought white people could have intelligence.”

Now, as an educator on the west side of O’ahu, Kiliona hopes to be the teacher he never had as a child: a teacher who affirms the identity of his students, and a teacher who shows young Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders what is possible for them by exposing them to scholars, writers, and professionals who share their background.

Research has shown that students benefit when they have a teacher who shares a similar identity and background. While just 2.5% of teachers nationwide identify as Asian American, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander (AANHPI), their impact in the classroom runs deep, as does their legacy as activists, organizers, and community leaders.

This Asian and Pacific American Heritage Month, we’re shining a light on the contributions of the AANHPI community toward the fight for educational equity. We asked four current or former AANHPI educators to share their personal stories about their experiences with AANHPI representation as students and as teachers, and their hopes for the future of education with increased AANHPI leadership in education.

Representation in the Classroom

My teachers helped to shape my identity

Pi’ikea Kalakau-Baarde (Hawai’i ‘15), Resource Teacher: I was very fortunate to go to a private school here on O’ahu that is specifically for Native Hawaiian students. I had many teachers that shared my identity. When I look back on my learning experiences, especially now that I'm a teacher, I realized it was my Native Hawaiian teachers who I really connected and resonated with, who helped me to shape not only my identity but what I wanted to put out in this world and how I wanted to do that.

Without AANHPI teachers, I struggled to understand my identity

Jiun Kimm (New York ‘10), Global Head of D&I at Samsung NEXT: I grew up in the rural South where there weren’t other students that looked like me. Racism was a familiar and defining aspect of my schooling, and as a young child, I rarely felt a sense of belonging in the classroom. I never had an Asian teacher from K-12, and the first time I saw one was in college. I think having an Asian teacher would have dramatically changed how I felt about my K-12 experience as school was where I most struggled to understand my Asian identity and feel like I was part of a community.

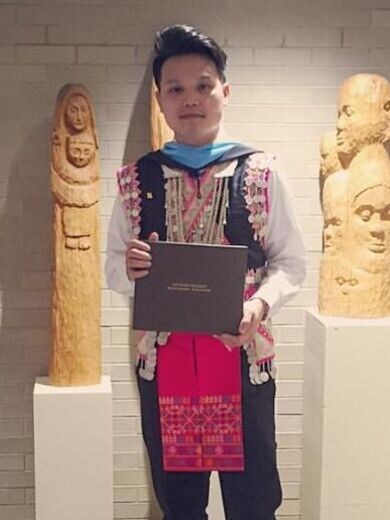

Levi Lovang (Milwaukee ‘14), Teacher: I didn’t have any teachers who shared my Hmong or Asian identity. I definitely think it would have been more positive, if I did. I think it would have helped me foster this self-confidence that I lacked in school all the way up through college. Instead, I had this constant feeling of alienation and desire to always want to fit in with the rest of the crowd.

Kiliona Palauni (Hawai’i ‘17), Teacher: I never saw a non-white teacher until I was a junior in high school. I had one Japanese teacher. I grew up in the diaspora. My dad’s Tongan, from Tonga, and Maori, from New Zealand. My mom is part-Hawaiian. I actually grew up predominantly in Idaho and Utah, not in the islands.

I’m Building Solidarity with Students--Across Lines of Similarities and Difference

Kiliona: I teach in an area where the vast majority of our kids are well below the poverty line. I'm one of the few teachers that is Polynesian and actually part-Hawaiian. Every day when I go to work, I wear dress shirts, dress pants, and dress shoes. I think that that really matters because not only am I like them, not only did I come up like them partly, but I'm also now an educator, educated, and I show up every day looking professional. It's an opportunity for them to see that they can accomplish more.

Levi: I'm almost always the first male, but also the first Asian teacher my students have ever had. I think that's a powerful thing. I like to think that we get to build solidarity across lines of differences. I’ve taught predominantly Black and brown students. Though I don't look like the students who I serve, having an understanding of my own marginalized identity allows me to help my students understand theirs. I think it helps us all reimagine what we would want the world to be like

Pi’ikea: I grew up in a very similar situation as a lot of my students, but I'm still an outsider in their community. It's different here in Hawai’i. I'm Hawaiian, but also Portuguese and Chinese, though I don't necessarily identify with that. For our students to see other Native Hawaiian teachers in their classrooms sharing their journey is very impactful for them. They can see someone who was raised similar to them, who shares the same values, who might even be related to them in some way or know the same people, have the same interests, same priorities.

I’m making sure students see themselves in the curriculum.

Levi: It's really important that I continue to educate myself in order to educate my students about the narratives and about the diversity of Asian America. I didn't really get into learning and teaching about AANHPI history until my third year teaching, but even then I had defaulted to teaching it just in May, right during Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. Now, I understand that everything's a learning moment. If we want to talk about the labor movement in the ‘60s, I can talk about Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta and the Farm Workers Movement early in the year, but we don’t need to wait ‘til May to learn about Larry Itliong, the Delano Grape Strike and the role of other Filipino farm workers as well. I'm always coming back to the bigger idea of solidarity and action

Pi’ikea: We try to look at ways that we could make things more relevant for our kids because the community that I teach in is very rural and extremely isolated. One example is argumentative writing: We chose to focus our unit around the homeless issue that a lot of our students face. We do have a fair amount of homeless students with huge problems here in Hawai’i. We had them watch a documentary, a local documentary on our homeless issue and all the controversial sides of it, and then they craft the arguments. Basically, just being an advocate for place-based learning. It's easier for us because Hawaiian culture is really dominant here.

Teaching students about anti-Asian bullying and xenophobia in the past and present

Levi: I think COVID-19 and the bullying, anti-Asian sentiment and racism that's going on is definitely a teachable moment to tie it to things that have happened historically in the past, like the Chinese Exclusion Act. I've shifted towards an approach where I study and teach history and contextualize it to what's happening today and how it's impacted marginalized communities. I do that sometimes through math lessons, through social studies. I do that mostly through our Social-Emotional Lessons, and I’m going to continue to do this.

Identity & Mentorship

The AANHPI community is not a monolith.

Jiun: As a leader working in tech, I work in an industry that gives the impression that Asians are, in fact, the model minority. The data in tech shows that Asians are overrepresented in the industry, which leads to the belief that this is proof Asians are thriving and have overcome the barriers of racism and discrimination.

However, this belief is problematic and does not tell a nuanced, accurate story of our community. The data we see about Asians in tech paints us as a monolith – like much of the data we tend to see about Asians – and is not disaggregated to show the vastly different experiences of Asians from a multitude of cultures and ethnic groups, with disparate levels of educational attainment, who speak different languages, and have varying immigration stories.

And even with high levels of overall representation in the industry, Asians still struggle in leadership representation – with some studies showing that, as a group, we are sometimes one of the least likely to make it to the top.

Most dangerously, the myth continues to be used as a wedge against other communities of color. I’ve definitely seen this seep into conversations in the tech space, with representation of Asians used as proof of successful recruiting efforts that ignore the inclusion of Black, Brown, or Native communities; or false narratives used to justify why Asians are “making it” in tech while other groups of color are not.

Connecting with my identity by rejecting the model minority myth

Levi: The model minority is what I had strived to be growing up as a child of Hmong refugees. Non-confrontational, smart, hardworking, prosperous, all at the same time. I had neglected parts of my cultural heritage because I didn't want to be associated with people in poverty or with immigrants. This is why I struggled to find myself and succeed in college right away. Now, I understand that I was socially conditioned to feel and think that way. If I didn't, I honestly don't know where I'd be or be doing right now. Teaching is my form of activism at the moment, among other things.

Having a mentor who shares your identity can make all the difference for students and professionals

Kiliona: As a kid, I didn't have any mentors other than my mom and dad to look to. If I would have seen people that looked like me or were like me succeeding academically and in sports--because I was really athletic in high school--I might've put those parallel connections of academics into those colleges. It would've been nice to see somebody, some role models, in higher education or in professional worlds, or teachers that defeated the odds and defied the odds and was successful.

Pi’ikea: I've had many mentors, whether they're in this specific field or just other business or professional fields here in Hawaii. Most of them have been women of color, of course, I think that's very important. They've been really impactful in the sense that they've helped me be more confident in what I'm doing and get rid of that imposter syndrome that a lot of us feel very quickly by just saying, "Hey, if not you, who, and if not now, when?” I can see the changes they're making, they're running for office and they're becoming all these great things in our community and doing things for everybody else. I see all of these women working together and it's really amazing to watch.

AANHPI Leadership in Education and Beyond

With more AANHPI educators and school leaders, we can advocate for the changes that we want to see.

Kiliona: I think it would open up a lot more opportunities to incorporate cultural lesson plans, real cultural lesson plans, creating a curriculum around our indigeneity. It's having that indigenous mindset that when you're making lessons, when you're making curriculum maps, it's all through this mindset of, “How am I going to teach about celestial navigation and wayfinding through the lens of Polynesians and not the lens of Western astronomy?”

It's picking books, not because they're Western scholars and everybody reads Of Mice and Men, but picking books written by our people, about our people, that perpetuate our culture, and then fielding seminars and discussions about those, and understanding what it truly means to be Hawaiian or being Laotian. They can see that we are also scholars, we're also writers.

Levi: I think that we'll see more discussion around the importance of having representation to help advocate for the changes we want to see in specific AANHPI communities, that we're not a monolith, that we are a diverse group of people. We can also help reimagine what that would look like in schools from a systemic level by incorporating more voices, from students, families and from the community. By having more representation in the different systems of change--whether it's school leadership or public policy--we have more access and we can gain more power.

Our activism will lead the community to a better future and it deserves to be seen.

Pi’ikea: At one point in time, Native Hawaiians faced extinction and we still do. On top of all these other issues we have in terms of education, work, housing, and everything else that everyone else faces, we also face extinction all the time because there are not a lot of full-blooded Native Hawaiians. That's why we're always pushing, we want our land back, we want these rights, and we need our reparations because we have fought back from a hundred plus years of injustice here, specifically in Hawai’i.

Jiun: AANHPI leaders play a critical role in the pursuit of justice because justice for everyone can only be achieved if we all play a part. While our community has struggled with visibility and having our stories told, we have a strong history of activism and, throughout history, our people have undoubtedly helped forge the path towards equity.

As a leader working in diversity and inclusion, if I’m doing this right, my work can empower all those who are marginalized and help build an industry in which access to opportunity and success is truly equitable. My AANHPI identity and my experience as an AANHPI teacher has instilled this belief in me. As a leader in this work, I constantly ask myself – “Is this a place where I’d want someone who shares my identities or want my students to be? Would they truly feel valued here? Would they feel like they belong?” If I can’t answer yes to these questions or say that the actions I’m taking are getting me there, then I’m failing.

Kiliona: I wish some more people realized how vital it is for indigenous youth to have indigenous teachers that understand their culture, understand their identity, understand their troubles. I wish that this is a profession that more people, especially Polynesians themselves, realized was needed. If we're not the ones educating ourselves, somebody else is, and then how can you complain when you don't like the way they're educating us? I wish more people would step up to the plate and lead our community to a better future.

Levi: Until we shift the narrative, we're going to be continued to be seen as like a monolith, and the perpetual foreigner which is being reinforced by a lot of the anti-Asian sentiment, bullying, and racism that we're seeing now during COVID-19. Liz Kleinrock, a Teaching Tolerance Award winner, said that we need to include Asians in our activism. We also need to unlearn everything we've been taught about the model minority myth and to educate students on identity and Asian American history in order to understand that our liberation, our humanity is tied to all people of color

Educational equity and justice cannot be achieved without AANHPI leadership

Levi, Pi’ikea, Jiun, and Kiliona are a part of a long line of educators, community leaders, policy makers, professionals, kūpuna and scholars, all of whom continue to build upon the legacy and achievements of the AANHPI activists and ancestors who came before them.

They’re tying today’s events to the legacy and activism of marginalized communities and fighting against the wedge that the model minority myth drives between professionals of color. They’re making room for indigeneity in the classroom and connecting environment and culture through place-based learning.

By bringing their identities into classrooms and the workplace, Levi, Pi’ikea, Jiun, and Kiliona are fighting to make an equitable education a reality not just for AANHPI students, but for all marginalized students.

“Revolutionary and ancestor, Grace Lee Boggs, once said, ‘You cannot change any society unless you take responsibility for it, unless you see yourself as belonging to it and responsible for changing it,’” says Soukprida Phetmisy, the Senior Managing Director of the Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) Alliances. “Throughout all of history, there have always been AANHPI folx fighting for equity alongside Black, Indigenous, people of color, and historically disenfranchised communities. Oftentimes, these stories of solidarity and activism have been invisibilized or erased. But we were there. We will continue to be there.”

“It’s important that AANHPI students and students who don’t identify as AANHPI also see us there—past, present, and future—and know there’s a long history of contributions to the fight for educational equity and justice,” she adds.

Sign up to receive articles like this in your inbox!

Thanks for signing up!

Content is loading...