Searching For A Third Way to Measure Success

Parents, principals, and (ex) district leaders are calling out to evolve how we measure student and school progress beyond math and reading scores.

When Sarah Guerrero (Houston ’07), principal of Northbrook Middle School in Houston, Texas, decided to shadow one of her seventh graders for an entire school day, it struck her that the core subjects she and her staff tended to obsess over seemed almost incidental to the way her students thought about school.

“It wasn’t that math and reading weren’t important,” Guerrero says. “That just wasn’t what was lighting their fire.” Instead, her students lit up when they talked about playing clarinet in the orchestra, writing poetry in a workshop with a resident artist, or riding on the bus with their volleyball teammates.

Such insights troubled Guerrero as she considered her school’s traditional seven-period day, comprised of five core subject blocks and two electives. Sixty percent of her students were English language learners, and two-thirds of the student body came in reading far below grade level. Guerrero knew they needed more remediation, but when to squeeze it in? She knew many schools had addressed the same quandary by swapping out electives for extra math and reading labs, but at what cost?

If Guerrero pursued that fix, it would mean the majority of Northbrook students would move through their days without the joyful sparks that made kids love school. Ultimately, Guerrero reconfigured the master schedule to have eight periods to ensure that every child could have at least two electives.

“It’s not a binary question—this over that,” she says. “We need to consider all of the things that are important to our kids. You can’t just think about math and reading data spreadsheets.”

Guerrero’s compromise reveals the tension educators—particularly those working in high-need schools—must navigate in trying to foster a rich and varied school experience while also ensuring their students master foundational skills like math and reading. It’s a tension compounded by the pressures of a testing culture that penalizes schools for missing achievement targets.

“To be successful, my kids absolutely need to be good readers and mathematicians,” Guerrero says. “But when we boil down the work of a school into two metrics, it can create a scenario where we expend resources, energy, and time on things that help bump those numbers in the short term but aren’t in the best interests of our students in the long run.”

Debates around test-based accountability are nothing new. But sharp criticisms have rarely come from leaders associated with education reform. That reluctance was rooted in a resolute belief that greater accountability would lead to greater equity. The influx of data under No Child Left Behind provided educators with an undeniable line of sight into disparities in student achievement across race, class, and disability. For the first time, parents had a way to see how their child’s school measured up to their counterparts in other communities. Ensuring that every student became competent in reading and math—the gateway skills that unlock so much other learning—became a matter of social justice.

More recently, however, even some staunch proponents of accountability metrics have begun to question whether the drawbacks of judging schools primarily on two metrics—math and literacy—outweigh the benefits. While the value of having standardized student achievement data is unambiguous, some education leaders are pushing for a more evolved approach to assessment—one that encourages practices and policies that will yield more meaningful results.

They’re looking to places like Hamilton Grange Middle School in Harlem, New York, to see how students are achieving fast gains on state test scores while spending significant time on arts, science, and carefully structured enrichments. The school’s founder and principal, Benjamin Lev (N.Y. ’04) rejects an either/or approach to curriculum, suggesting that when students can find a passion at school, “the learning part comes so much easier.”

One reason such schools are getting a hard look is that while the era of accountability launched by NCLB has yielded scattered successes among rigorous, high-performing schools and school networks in low-income communities, overall, as a nation, impressive returns at scale remain elusive.

A look at the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) over the last two decades reveals that, after a sharp rise in math scores during the early years of NCLB, gains have been relatively unremarkable. In the last decade, scores in both math and literacy have flatlined (and, in math, recently dipped) at underwhelming levels, with gaps widening between historically advantaged and marginalized groups.

In 2017, just over one third of fourth and eighth graders tested proficient in reading. In math, 40 percent of fourth graders and 33 percent of eighth graders cleared the bar.

Another impetus may be a growing sense of unease among practitioners as school priorities have shifted due to heavy focus on tested subjects. Here’s one stark example: Most high schools in New York City do not offer physics—a discipline many believe is the foundation upon which most other scientific study is built. Meanwhile, proponents of excellence have accelerated calls for students to hone habits of critical thinking and discourse, and develop social and political consciousness and leadership skills. They express a growing worry that these skills are being not just under-valued as drivers of higher achievement, but under-assessed.

Without broad access to the sciences, civics, arts, world languages, computer science, and the habits of critical thinking, will students truly be prepared for the work force of the future? And if not, are intensive efforts to raise math and reading scores doing enough to advance this fundamental civil right?

A Sharp Turnaround

Ten years ago, Paymon Rouhanifard (N.Y. ’03) would have answered that question very differently. From 2010 to 2012, he ran New York City’s office of portfolio management under then Schools Chancellor Joel Klein, a fierce accountability champion. Rouhanifard has described himself during those years as a “devout believer that every decision should be predicated on math and literacy tests.”

So it came as something of a surprise when Rouhanifard gave a speech at MIT in November where he said this: “If life outcomes are indeed what we are about, we should welcome state test scores going down.”

As he sipped a green tea at a Starbucks outside of Boston, where he recently moved with his family, Rouhanifard flashes a quick grin when asked about his comment. “That may have been the most provocative thing I said that day,” he says. “It was intentional.”

Rouhanifard has some leeway to rock the boat. In June, he stepped down after a lauded, five-year tenure as superintendent of Camden, New Jersey schools. Under his leadership, high school graduation rates surged, and the district halved its dropout rate and nearly tripled its math and reading scores.

In Camden, Rouhanifard says his views evolved because he deliberately left behind the echo chamber of policymakers and funders to spend time with constituents. He held teacher and student roundtables, frequented community events, and even volunteered as a coach in the city’s youth basketball league.

What he heard spurred him to partner with nonprofit organizations to provide wrap-around support services, mental health clinics, and trauma-informed care for students—urgent needs, to be sure, but ones that don’t immediately lead to better test scores. He also decided to scrap Camden’s school report cards that were primarily based on math and reading scores.

“We’re not always honest with ourselves about the decisions we’re making,” Rouhanifard says. “To me this is a lot about evaluating tradeoffs with the rigor they deserve.”

Rouhanifard says there’s no question that current accountability constructs have fueled a genuine drive for better math and literacy outcomes—including in Camden, where achievement scores were once in the low single digits. But he also believes the testing culture has created perverse incentives to prioritize short-term gains at the expense of long-term life outcomes for kids.

“Education is a public good that can’t be reduced to one or two measures,” he says. “We’re at a point where we should be evolving and creating a better version of ourselves.”

Students complained that they spent too much time taking tests. Parents wanted to know why their schools didn’t offer more sciences, languages, civics, or year-round art and music. Teachers, for their part, were deluged with data they could barely parse before the next assessment was upon them. Schools with greater numbers of English language learners, or students with Individual Education Plans were unfairly penalized with low ratings, and many schools routinely carved out large chunks of their instructional calendars for test prep.

Rouhanifard draws a contrast to how more affluent schools approach testing. “You talk to the parents there. The kids are taught, and they do well on the test, but they’re not taught to do well on the test. There’s a big distinction there,” he says.

Such schools operate with a different—and, Rouhanifard believes, more meaningful—calculus. By not overemphasizing tested subjects, their students enjoy a more engaging and comprehensive education—arguably one that prepares them better for life. “That’s what our kids are missing out on,” Rouhanifard says.

But is it realistic to expect that an under-resourced school facing significantly more obstacles can take a similar approach and get similar results? Instruction at these schools won’t look exactly the same, Rouhanifard concedes, “but they shouldn’t look this different. One shouldn’t be offering AP Physics and the other doesn’t offer any physics. One shouldn’t have every single art as an opportunity and the other does it one semester and that’s it, as a check-the-box. There is a happy medium here, and we’re not searching for it.”

Rouhanifard points to research by Stanford economist Raj Chetty (done while Chetty was at Harvard University) that suggests skills such as perseverance and getting along well with others may be more predictive than test scores when it comes to college persistence and income mobility. If true, it’s fair to ask: Are schools even measuring the right things?

Even as he hopes to see an overall reduction in testing and prep, Rouhanifard believes we need more normed assessments in vital subjects such as the sciences and arts. “We don’t value those things right now, but we should.” Meanwhile, he says states could reduce testing frequency to once every two or three years, using exams as a “dipstick” to expose gaps and address them.

Perhaps most importantly, Rouhanifard says we need leaders who can balance urgency with a grounded understanding of the complex problems schools face. “The challenges we inherit are so profound, they’re not as immediately fixable as we thought they were,” he says. “This whole three-year slope to 100 percent, and if it doesn’t get there, throw out the baby with the bathwater—that mentality needs to fundamentally change because we’re not playing the long game for our kids.”

Heather Harding (E.N.C. ’92) agrees there are problems with over-testing, but she cautions against a broader retreat from assessment and accountability. “The risk of backing away is that we won’t know where teacher quality is lacking,” says Harding, who began her career teaching middle school, held senior positions (including vice president of research) at Teach For America, and now leads work on education policy issues at the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation.

The lack of progress on student achievement “is a problem for sure, but we have a system right now, that if we stay with it, we can begin to unpack that.” Harding says. “We know, based on science, how well children should be progressing. We should be leveraging that to say, ‘If this is a good teacher, a good school, then they can get kids here. Accountability has to rest on the backs of education professionals who have chosen to serve families and students.”

That said, Harding favors reworking the current testing regime. “One of the central dilemmas we need to solve is that instruments we use for accountability are not actually useful to practitioners.” Too often, state exams—the same ones used to determine grades on school report cards—don’t test kids on what they actually learn in school, nor do they give teachers timely, actionable data. So districts, in turn, layer on additional tests in order to obtain relevant data that can be used to drive instruction, leading to more time spent on testing..

Harding believes that consistent accountability systems will be crucial as the global economy shifts toward automation and artificial intelligence. It’s no time to back away from standardized, comparable, baseline measures of student learning. “There’s going to be a great push to innovate” within schools and learning models will favor new technology, she says. “If we don’t have a grasp on how we know kids are learning, we’re going to be so lost in our ability to capture how our children are doing.”

Working on a “Third Way”

The quest for “the fewest and best” assessment tools is something of a fixation for Elliott Witney (Houston ’97), associate superintendent of academic design and performance in Spring Branch, Texas schools, where Sarah Guerrero is a principal. “The end-of-year state test isn’t actionable because the children have already left the building” by the time their teachers see the results, he says. “Some people refer to it as ‘autopsy data.’”

Along with 11 other school districts and charter management and education organizations, Spring Branch is working on the problem of “data interoperability,” or how to get data systems to talk to one another and give teachers actionable insights. In the last two years, Spring Branch has rolled out a multiple measures accountability framework to capture a more comprehensive picture of students’ preparedness for post-secondary success. Principals and teachers can access a wealth of academic growth metrics for every student—from PSAT scores to the MAP Growth assessment, which tracks a child’s progress through a school year—as well as attendance and discipline data and surveys that measure students’ interests and connectedness to school.

Witney says his district is also moving toward more personalization, with “proficiency scales” that break down learning standards into individual skills, enabling students to see their own progress in real time. “Contrast that with, ‘I’ve got a 72 percent in English,’” Witney says. “Instead of reducing a unit or a year to a single number, it empowers kids as learners to own their own path.”

One of the biggest challenges, Witney says, has been helping teachers learn to manage the wealth of actionable data and how to use it. He compared teachers contemplating this new mountain of data to a ship approaching an iceberg: “Once you know it’s there, it can feel a little overwhelming.”

However, early results are promising. In one middle school pilot with 100 sixth graders, one cohort of students performed 24 percent higher on the state reading exam and another cohort scored 33 percent higher in math. A student survey also recorded signficant jumps in the way students rated their connectedness to school and their perception of rigor in the classroom.

“We’re just starting this journey and it takes a lot of time at first,” Witney says. “But I heard a 20-year veteran say, ‘I’ll never go back to the other way.’”

A School Tries to Do It All

From April through the end of the school year, the 330 students at Hamilton Grange Middle School in Harlem, New York, submit to the usual gauntlet of standardized exams: English language arts, math, two tests for English language learners, science and additional eighth grade Regents exams in living environment and algebra. (Seventh grade tests are the primary metric used to determine high school admissions in New York.)

Last year, the school, where one fifth of students are English language learners and one fifth have disabilities, was honored by the New York City Department of Education for achieving the highest gains on the state exams of any middle school in the state. (The school’s most recent graduating cohort of eighth graders came into sixth grade at 13 percent proficiency in reading and 17 percent in math. They ended at 49 percent proficiency for both subjects.)

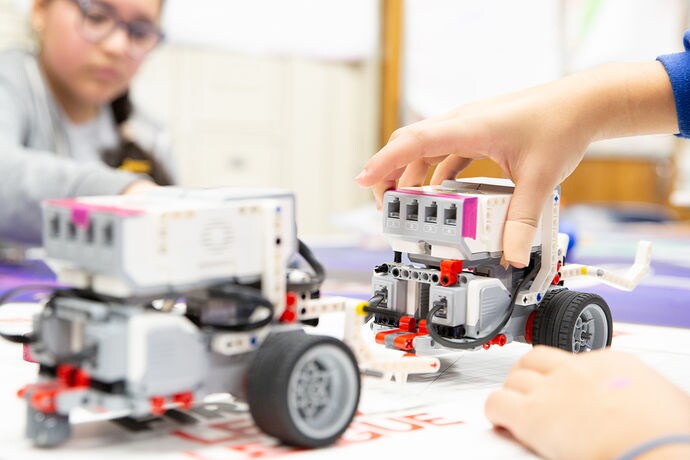

Hamilton Grange (HG) is noteworthy in another way. It prides itself on offering a vast array of clubs, athletics, and school-day electives. To name a few: debate, newspaper, LEGO robotics, band, spoken word, book club, hiking club, bouldering, track, basketball, soccer, softball, baseball, even boxing. Principal Benjamin Lev is running a school that sounds like the place Rouhanifard is describing, where test success is a byproduct of rich learning.

One thing HG doesn’t have: test prep. They don’t buy test prep books or teach test prep units.

“We want middle school to be a time where kids can find things they’re passionate about,” Lev says. “Then, even when the learning is really challenging, you’ve got all these other things you’re excited about—school doesn’t seem like such a slog.”

Students are explicitly taught and rewarded for eight “habits”—self control, tenacity, compassion, unity, service, justice, humility, and patience—which Lev says are skills that “correlate with success in relationships, career, school.” Lev also credits HG’s inclusive learning environment for the school’s striking gains. There are no self-contained classrooms. All students attend general education classes, and many have two-to-four instructors per classroom: a content teacher, special education teacher, an English as a second language teacher, and a speech teacher.

When a student, Crystal (her name has been changed for this article), came to HG in sixth grade, she knew just 10 of the 44 phonemes in the English language. In another school, she might be grouped with other students with disabilities and given simple, alternative texts to read. At HG, Crystal was streamlined into humanities with the rest of her sixth grade peers. “I was recently in her class during Socratic seminar,” Lev recalls. “I heard her arguing for why the Rosetta Stone should be removed from the British Museum and returned to Egypt.”

How did Crystal catch up so quickly? The short answer is: she didn’t. At least, not yet.

One perk of not focusing on test prep is more time for teachers to learn groundbreaking instructional practices. Every HG classroom uses a pedagogical approach that emphasizes academic discourse that engages peer and whole-group discussion over teacher-led instruction to foster learning. Rather than isolating some students in self-contained rooms with little access to grade-level content, HG immerses kids in academic discourse, giving them rich exposure to ideas, grammar, and vocabulary across disciplines. “We believe strongly in treating kid talk as a work product in the classroom,” Lev says.

When students read in class, a Google app on Crystal’s laptop reads passages to her while highlighting each word. When it’s time to write, she uses the same app that converts what she says into typed text. In other words, teachers are not waiting for Crystal to catch up before they expose her to grade-level content. They’re using grade-level content to help her catch up.

“She’s not yet an on-level writer, but she’s able to think critically about the texts being read to her, so she’s fully included in the grade-level thinking and discussion,” Lev says.

While progress at HG has been strong, Lev says the state scores are still a humbling reminder that less than half of his students are proficient in reading and math. Even so, he wishes the assessments weren’t such blunt instruments with such weighty consequences. “High-stakes tests are such a narrow indicator of what kids know and are able to do,” he says. “It would be great if the test was just a piece of the [high school] admissions puzzle, being that it represents two days out of three years of learning. It would be great my kids could be tested on the things they were actually learning. If they were, I know we would show far more than 49 percent proficiency.”

At the end of the day, Lev says he and his staff hold themselves accountable to this outcome: “We don’t become successful based on tests scores. If you leave our school really passionate about something and willing to work and be tenacious in pursuit of that passion—whether that’s being a killer trumpet player, a scientist, or a standout artist—then we’ve started to do our job.”

Sign up to receive articles like this in your inbox!

Thanks for signing up!

Content is loading...