Rosebud in Bloom

To meet the Lakota community's enormous aspirations for its children, Teach For America in South Dakota opened itself to tough feedback and changed its approach.

Mission South Dakota—Matilda Anderson is a tall, bespectacled eighth grader at St. Francis Indian School with the build of an athlete, the thoughtfulness of a scholar, and an adolescent’s propensity to see nothing but possibility.

“I want to be a pediatrician and come back to work for the Indian Health Service here,” she says. “And also to play in the WNBA.”

Matilda is Navajo on her father’s side and Lakota on her mother’s. She lives on South Dakota’s Rosebud Indian Reservation, which occupies 2,000 square miles of rolling grassland under sky as vast as the ocean. Since 1889, this tiny fraction of the land they once called home has been set aside by the U.S government for the Sicangu band of Lakota.

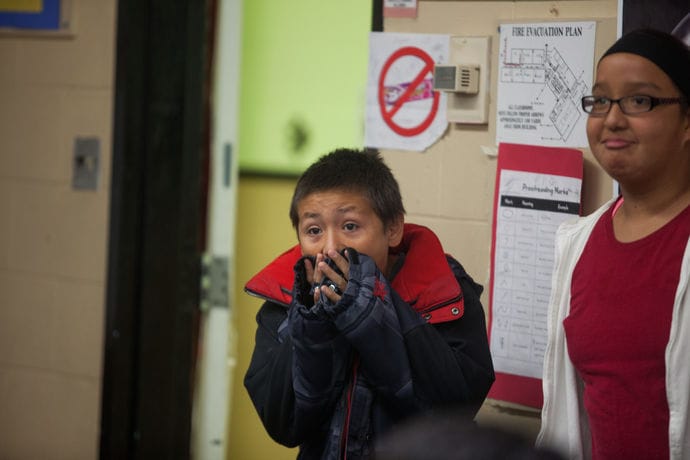

KRISTINA BARKER

Matilda has other dreams that are even less typical of most American teens. “Less suicides, because we have a lot of suicide around the reservation,” she says. And, “to get the Black Hills back.” The land was promised to the Lakota under the Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868, then reclaimed by the U.S. government after gold was discovered.

For Matilda and her generation, the bar for success is higher than a college degree and economic betterment. She feels the weight of her community’s deepest hopes that her generation will revive tribal health and sovereignty and save a language heading toward extinction. Scholars estimate the Lakota language is spoken by fewer than 6,000 mostly elderly Lakota people, of 70,000 tribal members registered in the U.S. and Canada.

In recent years, Teach For America South Dakota has broadened its vision to match the enormity of those aspirations. In South Dakota and on the Rosebud reservation in particular, Teach For America leaders have hired more American Indian staff members, recruited more Native corps members, and trained all corps members in the complex practice of culturally responsive instruction. The regional team is supporting corps members to engage more directly than in the past with community members so that when students succeed, the outcome is in line with what families demand. (Editor’s Note: This article ran in the Fall 2014 edition.)

“Student self-determination is critical. We’re shooting for kids to have the options to do what they want with their lives,” says Jim Curran (Phoenix ’05), the region’s executive director since 2011. In that way, Teach For America South Dakota has much in common with Teach For America everywhere. But on the reservation, “the ideal outcome is having the language and the traditional culture in a place where it’s thriving,” Curran says. “We’re pretty far from that point right now. But if you walk that back, it begins with this generation of kids in our classrooms.”

The challenges students and teachers face are enormous. Year after year, Rosebud ranks as one of the five poorest counties in the nation with unemployment hovering around 83 percent, according to the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs. Compared to all counties in the U.S., life expectancy here is in the bottom 25 percent among women and the bottom 10 percent among men.

Academic results, too, are among the nation’s lowest. In Todd County Public Schools, which enroll about three in four Rosebud students, the graduation rate is 49 percent. Ten of eleven district schools are labeled “priority” or “focus,” the lowest of the state’s achievement designations. At Matilda’s school, funded by the federal Bureau of Indian Education but operated by the tribe, 17 percent of students scored proficient on the mandated reading exam in 2012. In math, nine percent scored proficient.

But as Teach For America adapts its tactics, leaders hope to help teachers like Nicole Collins (South Dakota ’11) encourage more Matildas. “I pegged her from the beginning as an incredible student, super hardworking, with a super-supportive family,” says Collins, who teaches science. In August, with Collins’ guidance, Matilda won a scholarship that provides her with a private educational consultant through high school and full funding for anything related to academics, from a computer to an Ivy League summer camp.

The scholarship lends possibility to her most ambitious dreams, Matilda says. “It just makes me feel like…” she pauses. “There’s nothing stopping me.”

Teach For America's South Dakota office is on the reservation in the town of Mission, half a block from its only stoplight. Pick-ups and semi trucks rumble past along the main drag, Highway 18. Stray dogs and the occasional snake curl up on quiet, sun-warmed stoops along side streets.

In response to longstanding poor student outcomes, Teach For America has placed corps members in South Dakota since 2004, but it wasn’t until 2012 that the region placed such a high priority on hiring Native staff members, particularly those with local roots.

Curran characterizes Teach For America’s early years in South Dakota as foundation-building, but says it became clear that the organization would have to evolve in order to maintain local support. A growing ensemble of critics balked at the two-year teaching commitment, recalling a history of missionaries and reformers who came and went with the goal of dismantling rather than embracing tribal nationhood. Others felt some corps members acted arrogantly. “The fact is that our successful corps members have always connected with the community and to some extent engaged in culturally responsive teaching,” Curran says. “The fact is also that we haven’t done those things at anywhere near scale or optimal consistency.”

In late 2012, Rosebud native Dave Espinoza was hired as the region’s first manager of community investment, tasked with building support on the reservation for educational equity and the organization itself. He grew up in the town of Rosebud, where, at age 15, he was kicked out of his home to make room for his mother’s boyfriend. “I was that kid who thought nobody cared about me, nobody loved me.”

He overcame his turbulent past in part by learning about the historical trauma endured by his family and tribe, from their forced assimilation in boarding schools to the all-too-frequent legacy of abuse. “Our parents lost the ability to be parents because they were put into these institutions that didn’t have parents,” he says. As a young adult, he found a sense of identity in traditional Lakota spirituality. Today, Espinoza and his wife have six children, ranging in age from seventeen to one.

He draws on his life experiences to connect with Rosebud families in a way few outsiders could. On a given evening, he might accompany a corps member on a home visit, talk with parents at a local basketball game, or attend a school board meeting. He leads classes to empower parents to become active in their kids’ schools and to demand teachers hold students to high standards. He supports corps members in developing lessons and community projects designed to respect their students’ history and honor their families’ hopes.

Espinoza has had experience with the conditions of abuse and addiction that haunt many of the parents with whom he works. “How do you get people to see that outside of their box is a circle, and we’re all a part of it?” he asks. “We share this pride in being Lakota, we share this shame of being Lakota. Let’s bring it together, and let’s start moving.”

Soon after hiring Espinoza, Curran brought in Beau LeBeaux, an Oglala Lakota who leads community investment for the neighboring Pine Ridge reservation. Stacee Valandra, a Rosebud native and veteran kindergarten teacher, now manages teacher leadership development, coaching corps members in the same classrooms where her own daughter and Espinoza’s four oldest children attend school. Pine Ridge native Kiva Sam (South Dakota ’12) was hired to recruit more Native teachers and work with local colleges to build strong teacher education pipelines.

The team leads corps members, about 20 percent of whom identify as Native, through “identity work,” thinking and talking about privilege and race. “We’re having conversations about what it means to be a white educator on a reservation, but also what it means to be a black educator on a reservation, or a Native educator on a reservation that’s not your own,” says Tara Harrington, the region’s managing director of teacher leadership development.

Corps members must earn “credits” for attending sessions on Lakota history or philosophy or leading service projects. And in a push that began last year, they are coached intensively in culturally responsive teaching, an evidence-based practice designed to help students hit high academic marks while developing pride in their identity and a critical consciousness about the world around them.

“Culturally responsive” is a term most corps members wouldn’t have been able to define even a few years ago. But teachers like Abby Menter (South Dakota ’13) are steeped in its practice.

Menter teaches at Rosebud Elementary School, a 70s-era blond brick building surrounded by clusters of cottonwood and ash trees. On a Wednesday morning, her fifth graders sat on a rug reading from The Lakota Way: Stories and Lessons for Living, written by Rosebud native Joseph Marshall III.

“We’re going to be reading a story about courage,” Menter said. “But we’re also going to be learning about something called point of view.” When it comes time for state tests, The Lakota Way likely won’t show up, but “point of view” will.

For Menter, cultural relevance is key. She has seen that when students are personally invested in the subject matter, rigorous effort comes naturally. She describes a unit on boarding schools she developed with her students. Not only did they analyze historical texts above their assessed reading levels, they applied critical thinking to what happens when good intentions turn into harmful policies.

“A lot of my students have grandparents or great-grandparents who attended boarding schools,” Menter says. “It’s important for students to have ownership over that and see themselves as creators of a tribal nation, while also beginning to understand the anger and frustration that come from a history of oppression and pain.”

Menter has no plans to leave Rosebud. But as a non-Native from Ohio, the odds of her staying for the long term are slim. The reservation’s teacher retention problems didn’t start with Teach For America’s arrival, but neither has the organization improved them.

Kiva Sam, a manager of recruitment for Teach For America, was hired to change that, in part by recruiting local corps members from tribal colleges like Rosebud’s Sinte Gleska University.

Sam attended Little Wound School on Pine Ridge, the same school where she taught as a corps member. “Right now, our [Native] communities are really hesitant about Teach For America,” Sam says. “Partnerships are built, relationships are developed, but still there are so many teachers leaving after two years, and local leaders are left wondering if Teach For America is living up to what it says it can do.”

Cognizant of those criticisms, Sam is working with tribal colleges’ teacher training programs to strengthen their classes not just for potential corps members, but for all aspiring Native teachers.

In all, Teach For America has 100 Native corps members—up from 24 in 2009—due to a concerted effort by the organization’s Native Alliance Initiative, founded in 2010. Mia Francis (South Dakota ’14) came through the initiative to teach kindergarten at He Dog Elementary in the Rosebud town of Parmelee. She’s a member of the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe of the Iroquois Nation who grew up in a suburb of Philadelphia. She plans to make teaching Native students her lifelong profession.

“Growing up off the reservation, I struggled with my identity,” she says. “But you can grow up on the reservation and still not know who you are, depending on how you’re raised and what you’re exposed to.”

Throughout her childhood and into college, Francis was called upon to be “the token Indian” without knowing how to respond, she says. Now she feels she’s in a position to prepare her students for their first trips off the reservation, for college classes away from home. “If I can affirm them in who they are, they’ll be strong enough to face the dilemmas we face. Because they will face them."

Teach For America South Dakota’s reform efforts are recent enough that many critics haven’t taken notice, and families and teachers are divided on welcoming corps members into schools. (Valandra, the Rosebud native who manages teacher leadership development, says she’s not sure she would have noticed the changes either if she was still a classroom teacher rather than a staff member.) But among tribal leadership, support is growing: In July 2013, the Rosebud Sioux Tribal Council, the reservation’s 24-member governing body, passed a resolution supporting Teach For America’s work, a move Curran says would’ve been tough to imagine in the organization’s first years on Rosebud.

Wayne Frederick is a first-year member of the tribal council and a former guidance counselor at Todd County High School. For years, he had a bad impression of Teach For America. He recalls an interaction with a corps member who dismissed the idea of teaching tribal governance. “It’s like they didn’t understand what was going on here,” he says. But watching the evolution has turned Frederick into a backer. “They’ve gotten progressively, shockingly better,” he says. “Now is when the dividend will finally start coming.”

Curran says the team didn’t create a vision so much as tie itself to one that’s been in place for more than a century.

In 1923, John Neihardt published Black Elk Speaks, a book based on interviews with the revered Lakota medicine man. The text—a perennial inclusion on college syllabi—bears witness to the destruction of the Lakota way of life at the turn of the 20th century. But it’s part prophecy, too, recounting Black Elk’s vision for the redemption of his people at the hands of what many now call the Seventh Generation.

Prophecies suffer no shortage of interpretations, but many Lakota believe that the Seventh Generation—those born with the gifts to revive what has been neglected and find what has been lost—is the generation of young people alive today. Kiva Sam grew up hearing about her generation’s role, and she believes in it. But having earned a degree in government, she has seen that nations don’t revive just because a prophet said they would. “I consider myself a realist,” she says. “I like the idea of striving toward a hope and seeing the positive, but I know there are a lot of things we need to get in place.

“We have the potential,” Sam says. “We’re on the path. But we’re not there yet.”

Sign up to receive articles like this in your inbox!

Thanks for signing up!

Content is loading...