Afro-Latinx Students Navigate Racism and Erasure in the Classroom

Educators need more data and resources to understand these students. Inclusive curricula can help the students better understand themselves.

When her reading scores skyrocketed a couple of years ago, Dakota Pouncie says she wasn’t praised or celebrated. Instead, “I got undermined for my academic ability,” said Pouncie, a high school senior in Connecticut, who is Afro-Latina.

She says her white teacher told her: “You don't look like the type that could do that. You don't look like you're paying attention in class.”

“I always (got) 100s and 90s in the class,” Pouncie said. She remembers wondering why the teacher would doubt her.

This is just one example of how Pouncie says she has been stereotyped at school—by teachers and peers—because of her dual identities. Light-skinned or white Latinx students have questioned Pouncie’s Puerto Rican roots, from denigrating her darker skin color and tightly curled hair texture to calling her a “no sabo kid” because she’s not fluent in Spanish. A counselor, she says, wrongly assumed she was being abused or her family was struggling financially.

She’s not alone. Experts and teachers say many Afro-Latinx students face racist treatment. They are often made to feel invisible in interactions with students and school staff. They are erased in the way education data on Latinx students is collected and used and in curricula taught in classrooms across the U.S.

More than a quarter of students enrolled in U.S. public schools are Hispanic, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Research on Latinx students, however, does not account for racial distinctions within that ethnic group. Such a monolithic category makes it impossible to fully track the academic performance of students who are Black and Latinx as well as other challenges they may face and disparities tied to systemic racism.

“When you don't have data that is able to be disaggregated to see the ways in which race, anti-Blackness, is having an effect on some Latino students differently from those who are white appearing, you're not able to measure and account for that problem and then address it,” said Tanya Katerí Hernández, a law professor at Fordham University who researches anti-Black bias in the Latinx community.

“If you're not able to detect these differences in how resources are allocated, how benefits are accorded, and access to special programs, then you're not able to intervene and make changes.” And there is clearly much that needs changing, Hernández says. She has found many examples of biased treatment of Afro-Latinx students in her research, from bullying to discipline disparities and Latinx teachers bringing their anti-Black bias into managing a classroom. The goal, she said, is to raise awareness of these issues and work to solve them to make sure Afro-Latinx students are seen and get the support they need.

The Need for Afro-Latinx Inclusive Curricula

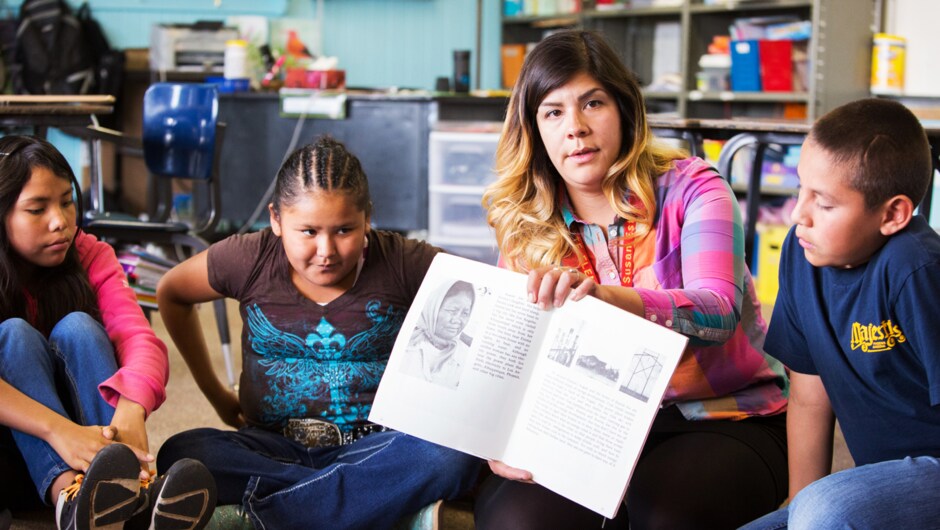

Erasure of Afro-Latinx history and culture in school and society is a major obstacle to reaching Afro-Latinx youth, educators say. It’s difficult to connect with and engage students who are Afro-Latinx if they don’t see themselves represented in curricula and broader pop culture references. That’s why educators like Álida Reyes (Greater Delta: Mississippi and Arkansas, ’16) are intentional about presenting more diverse representations of Latinx people and cultures in their lessons. She emphasizes that people who are Black, Indigenous and Asian—as well as their cultures and languages—are part of Latinidad, or a contested concept meant to build solidarity among Latinx people.

Latinidad aims to unite Latinx people under one term and identity “despite varying nationalities, racial and gender identities, generations, languages, immigrant status and mobility,” according to an article by Remezcla, a U.S. media brand focused on Latin culture. But some argue Latinidad upholds white supremacy and celebrates “mestizaje,” or mixed-race heritage that centers whiteness. The closer a person is to that ideal, the more privileges and access they obtain in education, civil rights, and socioeconomic status.

“It's important to investigate how Latinidad upholds whiteness and proximity to whiteness so that (Black) students themselves start being able to feel included under Latinidad,” said Reyes, who is Afro-Dominican.

“It's hard for me to say I'm Latina. What does that mean? What do I have in common with somebody from Colombia? The Spanish language? I have more in common with somebody from Trinidad and Tobago, because they're island people and they were colonized and they were sugar cane growers like we were.”

Reyes says Latinidad’s Eurocentric and mestizaje beauty standards play out in the classroom, as students try to over-identify with Latinadad at the expense of their Blackness.

“When people are referring to Afro-Latinos, you always see the light-skinned girl with soft curls,” said Reyes. “I have students that are 16, thinking about surgery, thinking about getting hips or getting lipo. My girls were blow drying their hair. It's hard to watch sometimes when they even buy lotions that lighten their skin.”

Get more articles like this delivered to your inbox.

The monthly ‘One Day Today’ newsletter features our top stories, delivered straight to your in-box.

Content is loading...

Erasure and anti-Blackness are baked into the geographical and common demographic concepts of Latin America—concepts reinforced by school curricula that do not include comprehensive information about Latinx people, history and cultures.

Historians estimate that more than 90% of about 10.7 million enslaved Africans who survived the Middle Passage were sent to Spanish and Portuguese colonies; about 3.5% were taken to U.S colonies. Today, about 133 million people of African descent live in Latin America , making up roughly a quarter of the total population, according to the World Bank. Mexico only began officially counting its Afro-Mexican population in its 2020 census—and that’s true despite the fact that the nation’s second president, Vicente Guerrero, was Afro-Mexican and abolished slavery. Latin America and the Caribbean encompass more than 30 countries where languages such as Nahuatl (Mexico), Portuguese (Brazil) and Haitian Creole are spoken. Brazil is home to the largest African and Japanese diasporas in the world. In the U.S. alone, there are 62.1 million Hispanic people. One-quarter of the U.S. Hispanic population self-identify as Afro-Latino, Afro-Caribbean or of African descent with roots in Latin America.

Even in English as a second language classes, students are typically taught the Castilian dialect spoken in Spain, not taking into account the different dialects spoken by the African diaspora that are often excluded from Latinidad. An academic study published in January analyzed 12 beginner-level Spanish textbooks and categorized the findings as an erasure of Afro-Latino identity and culture. In the few examples of Afro-Latino representation, researchers found instances of colorism, racial stereotypes, collectivization, and tourism discourse. Tourism discourse reduces Afro-Latinx culture to what can be commodified or consumed by tourists—such as singers, dancers, and entertainers—while omitting historical and political information.

Reyes, a former ESL student, says students fall behind in mastering English when one dialect dictates how materials are translated. Reyes said she feels that teachers are not equipped or trained to address the linguistic and cultural needs of Spanish-speaking students from the Caribbean.

“Caribbean students, Dominican students, the way that they communicate, they're loud,'' said Reyes, an equity consultant and creative writing graduate student. “It's very flamboyant. A lot of times that is read as improper for school. Your Spanish is not good enough. You get kicked out of the classroom for simply speaking.” Reyes notes that this reinforces the school-to-prison pipeline.

Interested in Joining Teach For America?

Erasure is not only present in language instruction but also in history curriculum. That’s why Reyes—who also teaches Spanish online—is educating students about the Haitian Revolution's role in liberating Black people across the Americas and jumpstarting the independence movements in Latin American countries. Reyes also discusses problematic depictions of Afro-Latinx people in present-day Latin American soap operas that place Black actors in servitude roles.

A New Focus on Black and Latinx Studies

Emily Gardín, who is Afro-Panamanian, felt more confused than excluded by K-12 lessons when she was a student in Waterbury, Connecticut.

“It made me ponder a lot, if someone that looks like me accomplished something, what would be said about us?” said Gardín, who graduated last year from Emory University with a bachelor's degree in African American studies and a minor in Latin American and Caribbean studies. “Maybe Afro-Latinos just haven't had the platform” or “visibility to be recognized for their accomplishments?”

In 2020, Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont signed into law Public Act 19-12, which required schools in the state to offer elective classes on Black and Latino studies. The requirement goes into effect this fall. This is the type of class that could have helped Gardín see herself and her culture in what she was learning. She might have benefitted from the lessons on Afro-Panamanian women fighting for Canal laborer’s rights and content that pushed against the country’s Eurocentric beauty standards. Gardín would have welcomed a course that drew comparisons between the experiences of the African diaspora in the United States and her native Panama. However, these were lessons she had to learn outside of the classroom.

Gardín’s great grandfather was among West Indian laborers who built the Canal Zone.

“My dad worked in the Panama Canal, so he told me stories of segregation, and they had their set of race issues in Panama. We do have family members that were affected by enforced or cheap labor; we're still oppressed by similar systems,” she said.

More than 75% of Panama Canal laborers hailed from West Indian islands like Jamaica and Barbados. Laborers were segregated, with people of color getting lower wage jobs in dangerous working conditions and inferior housing to white employees. The West Indian workforce did the backbreaking manual labor: cutting brush, digging ditches, dynamiting and unloading equipment.

Pouncie, the Connecticut high school student, is taking the new Black and Latino studies course. Her school is one of 50 across Connecticut piloting the curriculum this year. She was surprised to learn about the Tuskegee Study in which U.S. public health officials experimented on Black men infected with syphilis and withheld treatment from them, and about redlining. Such topics were never introduced in her previous history classes, which instead heralded figures like Christopher Columbus. The second semester of the course focuses on Latino history with an emphasis on Puerto Rican history. It includes lessons centering Afro-Latinx history, identity and culture, from the Haitian Revolution to the differences between slavery in the United States and Latin America. The curriculum also features videos and podcasts on topics ranging from bomba, the African diasporic dance in Puerto Rico, to the Afro-Indigenous community known as the Garifuna in Honduras.

Pouncie’s history teacher Adrian Solis instructs three sections of Black and Latino Studies. A majority of Solis’s 33 students are Latinx, while four white students, one Black student, and one multiracial student elected to take the course. The course should be a graduation requirement, not just an elective, Pouncie said. She says it would help combat the racism still displayed at school.

For example, in February, a white classmate at Pouncie’s high school shared a Valentine's Day card on social media that said "You take my breath away" with a picture of George Floyd, the Black man who was murdered by a white Minneapolis police officer, Derrick Chauvin, in 2020.

“I don't feel like I'm part of a safe space,” Pouncie said. “If we don't talk about this stuff, then it'll get lost in history. It’s good for more people to be aware…so we cannot make the same mistakes.”

The majority of students were unaware of the social media post, said Kerry Markey, a spokesperson for Connecticut Technical Education and Career System, which operates the high school Pouncie attends.

“The students that were identified in the post were disciplined in accordance with district policy,” Markey said. “As a means to give students voice and a platform to discuss these types of issues, the school has implemented an advisory program.”

The first session of that program was held the week of March 28 and focused on racial inequalities, Markey said.

Policed and Stereotyped By School Staff

Anti-Black bias in schools also leads to the disproportionate discipline of Black students, including those who are also Latinx. That’s one reason why Gardín is advocating for the Counseling Not Criminalization in Schools Act, federal legislation that would provide resources for robust mental health resources for schools in replacement of school law enforcement officers there. She wants to end cases like that of Alma Yadira Cruz, a Black Puerto Rican girl with special needs who was 11 in 2017 when she was charged with five counts of assault against classmates who she said bullied her. For two years, classmates harassed Cruz, calling her racist slurs such as “negra sucia” (dirty “Negro”), “pelo de caíllo” (twig hair) and “mona” (monkey), according to reports from Univision and Remezcla.

“This is in a public school in Puerto Rico. The racial harassment is unceasing, and the school doesn't intervene at all,” Hernández, the author and Fordham law professor, said about Cruz’s case. “The schoolteacher views the victimized Black child as the problem, brings in law enforcement on an 11-year-old child, and has her detained. And it takes another year or so of social justice awareness campaigns and lobbying to have the charges dropped.”

White educators are not the only ones susceptible to perpetuating anti-Black bias, Hernández said. Members of the Latinx community can be just as dangerous. In her forthcoming book, “Racial Innocence: Unmasking Latino Anti-Black Bias and the Struggle for Equality,” Hernández said she unpacks the misconception that people who are Latinx are exempt from racism due to their ethnicity and multicultural background.

“Latinos who are not self-aware about interrupting their own racial biases operate on the idea of the Afro-Latino student as more of a behavioral problem and more prone to needing outsize forms of discipline,” Hernández said. “For the child who's in a classroom in which they're being viewed differently, they are also being viewed as lacking the same kind of capacity. You're basically letting them know you're not welcome here within the educational context.”

Gardín has her own personal experience of biased discipline. Some teachers “definitely punished me or policed me,” she said.

Gardín recalled when she was in second grade and received discipline cards for acting out or talking too loud. “What made it difficult was my mom and my dad didn't know any English growing up,” Gardín said. She had to have her parents sign the cards, but ”they didn't understand the severity of it either. They didn't understand the school system itself.”

While in kindergarten and first grade, Gardín took ESL classes, but that support did not continue when she was in second grade. The mental health resources and evaluations that she desperately needed were also not available.

“Now that I'm an adult, I know that I was going through depression and... dealing with a lot of trauma as a kid, too,” said Gardín, who was also exhibiting neurodivergent symptoms as a child. “It wasn't flagged. They just thought that I was just being disobedient.”

When Pouncie was 5 years old, her father was arrested. After that, a school guidance counselor stereotyped and began pestering Pouncie and her younger brother for almost eight years, she said. During a home visit, the counselor wrongly assumed Pouncie’s mother was renting. There are obvious racial undertones to the assumption “because my mom was in her 30s and was financially stable,” Pouncie said. “There is no reason why she wouldn't own that house.”

Pouncie felt that the guidance counselor had a white savior complex. The counselor frequently asked Pouncie and her brother if they were being abused. She also seemed to “think that my mom was poor and struggling, that we always needed help, but we didn't,” Pouncie said.

These stories are no surprise to Hernández, who heard similar examples of racial biases faced by Afro-Latinx students in her research. She interviewed students from pre-K to college, as well as teachers and administrators across the country. One example she came across was a white Latinx teacher who had Black students, including Afro-Latinx students, “segregated into a separate part of the classroom with the presumption that a special ed teacher would attend to them.”

That was true, Hernández said, “regardless of whether or not they actually have an IEP (individualized education plan) and are diagnosed as having learning differences.” She even saw this trend when speaking with educators who trained Latinx teachers.

“This invisibility and this refusal to acknowledge it, this denial of the way anti-Blackness operates within Latino communities, also adversely affects trying to educate Latino teachers,” Hernández said. “They don't want to be called to account for their own anti-Blackness, and then we're sending them out into the field to engage students. That's a recipe for disaster.”

What’s needed, Gardín said, is advocacy, awareness, and documentation of Afro-Latinx student experiences. This is the work she’s dedicated to as an Afro-Latinx Líderes Avanzando Fellow, a program for first-generation college students “who are passionate about racial equity and making meaningful change in their campus community, workplace, and beyond.”

The way forward is by “making sure that Afro-Latinx students have resources,” she said. “So always include them in annual reports, (make) sure that we're gathering census data or just data in general about them.

“Make sure that our existence is being highlighted, talked about, and we're being represented and understood.”

Editor’s note: This article contains several terms to refer to people of Latin American descent. One Day prefers to use the inclusive term Latinx, but we also respect individual preferences such as “Latino.” We used “Hispanic” when matching language from an official source.

We want to hear your opinions! To submit an idea for an Opinion piece or offer feedback on this story, visit our Suggestion Box.

Sign up to receive articles like this in your inbox!

Thanks for signing up!

Content is loading...