Lessons About Black August Also Teach Students to Push for Meaningful Change

What started as a way to commemorate incarcerated Black leaders can be a gateway for K-12 educators to teach students about history and revolution.

At the start of each new academic year, teachers walk students through classroom expectations and procedures. It's an essential step, and you're setting yourself up for failure if you don't.

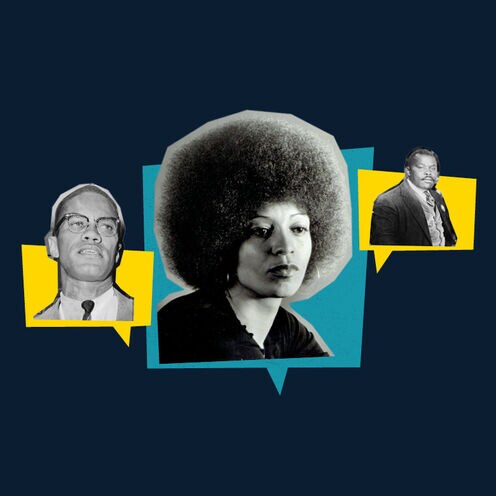

But what if we also broadened our idea of what’s “essential” for the first days of school to include establishing a more accurate portrayal of history? What if students' first lessons of the semester included reading quotes and texts from Malcolm X, Marcus Garvey, or Angela Davis? What if they engaged in dialogue about prison reform, food deserts, and the Black maternal health crisis?

That sort of education is also a necessity. When students can identify, analyze, and challenge systems of oppression and inequality in their communities, it’s what master educator Gloria Ladson-Billings calls a “critical consciousness.” Fortunately, there is a timely commemoration that we can use as guidance and historical instruction on the best ways to stand on the side of truth and properly confront the newest iteration of white supremacy that demands doing the opposite.

It’s called Black August, and most people have never heard of it.

You might be thinking, as I did when I first heard about it, that Black August is a relatively new phenomenon that emerged as a response to the 2020 murder of George Floyd by a police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota, or the fatal shooting of Breonna Taylor by police officers in Louisville, Kentucky that same year. (Still waiting on those convictions by the way.) Actually, Black August was established in 1979, and since then it has been practiced by communities around the country dedicated to the liberation of Black people. It was started at California’s San Quentin State Prison by incarcerated members of the Black Guerrilla Family after the killing of George Jackson, the group’s founder and leader. Jackson and two other incarcerated men originally created the Black Guerrilla Family in 1966 as a way to foster Black power and empowerment.

At first, Black August was used as a time to reflect on and honor the lives of incarcerated Black activists. Practitioners would spend time studying revolutionary texts, fasting, exercising, and abstaining from drugs, alcohol, and mainstream media. Over time, the celebration has expanded to not only involve studying and bringing awareness to works by revolutionary authors but also to encourage engaging in activism on behalf of incarcerated Black political prisoners and oppressed Black people around the world.

“Now is not the time to shrink in the face of oppression, but to stand tall on the shoulders of our ancestors who have paved the way for our liberation.”

Teachers looking to engage students in culturally relevant lessons on social justice, anti-racism, and community engagement can find inspiration from practitioners of Black August. A civics teacher looking to expose students to the issue of lack of access to healthy food options in low-income areas might have students analyze the Black Panther Party’s free food programs and devise their own solutions. Or an English teacher can have students read and analyze works from Black Power activists like Kwame Ture, Angela Davis, and Fred Hampton, and have them write an essay describing their own definition of Black power. Black power is a notion for all people to grapple with—not just Black students or Black people—so that there can be dialogue to help dispel implicit fears around what it means to empower Black people and what a world like that would or should look like.

Educators can also teach students about revolutionary and historic events concerning the struggle for the liberation of Black people that occurred in August. The Haitian Revolution began in August 1791, Nat Turner’s rebellion occurred in August 1831, the March on Washington took place in August 1963, and the Watts rebellion took place in August 1965. Additionally, a myriad of Black activists and leaders such as James Baldwin, Marcus Garvey, Anna Julia Cooper, and Marsha P. Johnson were also born in August. The addition of these revolutionary people and events to classroom curricula not only exposes students to different schools of thought surrounding the pathways to Black liberation, but also adds variety to the uniform list of Black historical figures like Martin Luther King Jr., Harriet Tubman, and Rosa Parks, who students are inevitably exposed to myriad times throughout their educational careers.

Get more articles like this delivered to your inbox.

The monthly ‘One Day Today’ newsletter features our top stories, delivered straight to your in-box.

Content is loading...

Just as the early practitioners of Black August in San Quentin faced reprisals from prison guards, we know that in today’s educational climate, teachers across the country are being targeted by school boards, lawmakers, and others for teaching the truth to their students about the facts surrounding this country and its inception. But what better way to teach about revolutionaries than by being a revolutionary! Students look to us, their teachers, mentors, and role models, for guidance on how they should engage with the world around them. As the state of our world seems to deteriorate with every news cycle, it’s an ideal time to use Black August as an entry point for teachers and students alike to engage in dialogue and practices focused on changing the conditions in their community and the larger world around them. The time to act is now, we can wait no longer because as George Jackson said, “patience has its limits. Take it too far, and it’s cowardice.”

Now is not the time to shrink in the face of oppression, but to stand tall on the shoulders of our ancestors who have paved the way for our liberation.

Just as the effects of systemic oppression and racism are not confined to a single month of the year, neither should the teaching of ways to fight and dismantle those systems be relegated to the month of August. Black liberation will never be achieved if we sit back and rest on our laurels 11 out of the 12 months of the year; the struggle must be constant, unyielding, and, as South African activist and revolutionary Oliver Tambo stated, “the fight for freedom must go on until it is won.”

We want to hear your opinions! To submit an idea for an Opinion piece or offer feedback on this story, visit our Suggestion Box.

The opinions expressed in this piece, and all others in our Opinion section, represent those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the Teach For America organization.

Sign up to receive articles like this in your inbox!

Thanks for signing up!

Content is loading...